Dawn, The Review, November 23-29, 2000

‘Listen to the flute. How it tells its story and complains of separation. It says, I have been crying ever since I was chopped off the reed…’

‘Listen to the flute. How it tells its story and complains of separation. It says, I have been crying ever since I was chopped off the reed…’

Thus opened the Mathnavi of Rumi, the favourite reading of Babur’s father Umar Sheikh besides the Holy Quran. Umar Shiekh used to spend long hours with his father-in-law Younus Khan, a descendant of Genghis Khan and a renowned scholar. The discussions of these elders left a lasting impact on Babur’s mind.

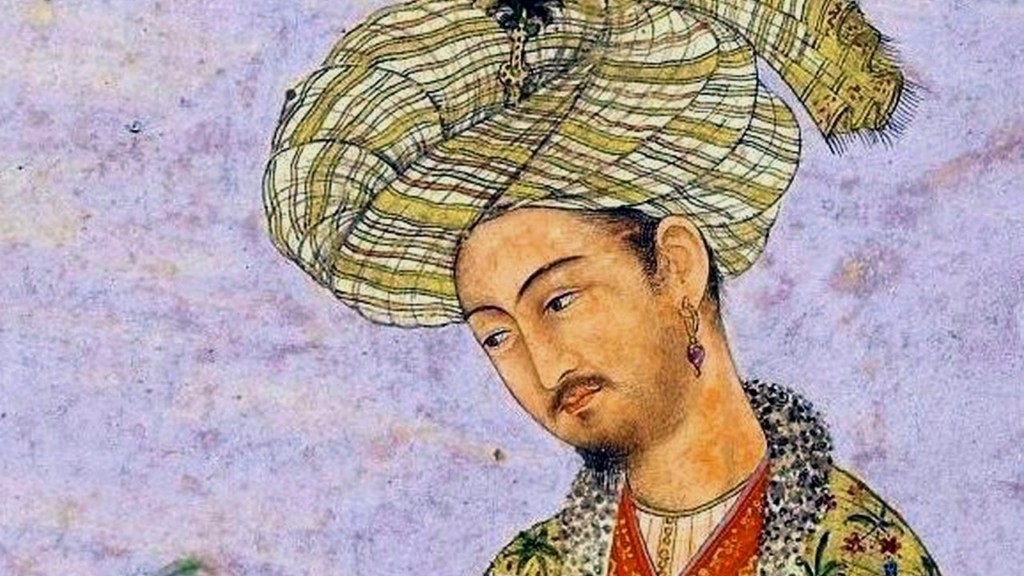

Babur’s role model, however, was a romanticized image of his ancestor Taimur, as presented in Zafarnameh, a eulogized biography of the conqueror and the plethora of family myths that had gathered round the personality of Taimur by the time Babur was born on 14 February 1483. Nevertheless it inspired him to become an excellent athlete and swordsman. His given name was Zaheeruddin but even in his early years he was known for a fierce style of fighting and hence he was nicknamed Babur (Tiger in Turkish). In his later days he could carry two men while running on the rampart, swim across all the rivers of India and defeat several enemies in a single combat.

His knowledge of the arts of war served him well because his father, the ruler of Farghana, died when Babur was eleven, and the small city was attacked first by Babur’s paternal uncle and then by his maternal uncle. Defeating two enemies before he was even thirteen gave Babur the confidence to attack Samarkand, the city of his dreams. He captured it in the second invasion, but not for long. Younger brother Jahangir revolted in the hometown and as Babur went back to meet him, he lost Samarkand too.

For a year Babur wandered as a virtually homeless prince. This was a familiar pattern in Babur’s life throughout his teens – taking a city from his friends or enemies and then losing it again. He learnt the excitement of building a fortune, right from the scratch, and then losing it to start over again. He turned a poet, and his outlook towards life was described in one of his lines that have become proverbial since then: Babur b’aish kosh keh alam dobareh neest! (O Babur! Better seek to be happy for the world is not to be again!). He learnt how to live each moment of his life. When a moment passed on, whether happy or sad, Babur moved along with it too, never looking back.

The secret of his survival was his gift for reading souls. He always picked up the right friends and oozed out his love for them. His one flaw, which he failed to see until very late in life, was his desire to become a second Taimur, though a far more civilized one. What price Babur paid for his mistake, and how he learnt the lesson, makes an interesting story. And Babur himself is willing to tell it first hand, even today:

‘In the month of Ramzan of the year 899 (AH) and in the twelfth year of my age, I became ruler in the country of Farghana…’ Thus began one of the most fascinating autobiographies, Baburnameh [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][or Baburnama]. Written in chaste Turkish prose, the book is remarkable for its irreverent honesty.

Thanks to Baburnameh, we can make a safe guess that Babur was either probably a virgin or uncomfortable with his own sexuality when he got married to his cousin Ayesha Sultan Begum at the age of seventeen. ‘I was quite attracted to her. Yet, this being my first marriage, out of modesty and hesitation, I used to see her once in 10, 15 or 20 days. Later, when my desire for her weakened out too, my hesitation increased. Then my mother Khanum used to send me, once a month or every 40 days, after much persuasion…’

Babur had a distinct feminine side too. He had delicate features and had begun his reign under the guidance of grandmother Aisan Daulat and mother Qutlugh Nigar Khanum. Soon after his marriage he found himself in love with a boy!

‘His name was Baburi,’ Babur notes down in his memoirs. ‘Out of modesty I could never look straight at him; how then could I make conversation or recite poetry to him? One day, during that time of desire and passion when I was going with companions along a lane and suddenly met him face to face, I got into such a state of confusion that I almost went right off. To look straight at him or to put words together was impossible … In that frothing up of desire and passion, and under stress of youthful folly, I used to wander, bare-head, bare-foot, through street and lane, orchard and vineyard. I was hospitable neither to friend nor stranger, took no care for others or myself. I was not in control…’

The Uzbeks, traditional enemies of the House of Taimur, invaded Samarkand under a powerful leader Shaibani Khan. Babur, a practicing astrologer, decided his war strategy in accordance with calculations from the Ephemeris of Ulugh Beg, and lost. He barely saved his life by offering his elder sister Khanzadeh in marriage to Shaibani.

So far Samarkand had been the reason for his existence. It seems that the humiliation cured some of Babur’s starry-eyed romanticism and when he captured Kabul in 1501, he took some realistic steps. For once he reconciled with the idea of an empire with Kabul, and not Samarkand, as its centre. Three years later he assumed the title of Padishah. By that time he had sorted out many of his earlier confusions, and even learnt to take pleasure from women, which was the distinctive trait of the House of Taimur. He had several wives by then and as his favourite one, Maham, gave him a son in 1508 Babur named him Humayun. In Persian it meant one favored by Huma [or Homa], the legendary bird whose shadow makes anybody a king.

In Kabul Babur followed his delicate tastes in architecture. An amazing example was the famous garden where pools were filled with wine, and the advice inscribed on the walls was, of course: ‘O Babur! Better seek to be happy, for the world is not to be again!’

With Kabul as his capital it was possible for Babur to plunder the wealth of India. From 1505 Babur started a series of raids on the villages and towns in the Kohat, Dera Ghazi Khan, and later, Bajor, Swat, Bheera and Khushab. During his first attack he followed the example of Taimur and massacred the inhabitants. However, his very nature revolted against barbarity and afterwards he allowed himself to be his own self.

Babur fell into the trap of his dreams again when in 1510 the Safavid Persian emperor Shah Ismail I became his friend. Babur, though himself a Sunni, agreed to introduce several Shia reforms in Samarkand if Shah Ismail could help him capture the city. This unleashed a religious war against Babur and Samarkand was gone again, this time for good. But the visionary in him woke up once his soul was freed of imitating a dead ancestor.

On 21 April 1526 Babur met one hundred thousand men of Ibrahim Lodhi with twelve thousand of his own at the famous Battle of Panipat and, with his gunpowder he defeated the enemy in a most remarkable display of military genius. Ibrahim made a desperate fight but got killed. Babur went up to corpse, lifted up its head and said, ‘Honour to your courage!’ Then he ordered a respectful burial for the dead king exactly on the spot where he had fallen in the battlefield.

Among the allies of Lodhi who fell was one Raja Bikramjit whose family possessed the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond. When Humayun marched upon Agra he impressed the dead Rajah’s family with his generosity and they presented him the famous diamond with a typically Indian exaggeration of its worth: ‘It equals the value of two and a half day’s food for the whole world!’ When Humayun offered this priceless diamond to Babur he merely looked at it once and returned it to Humayun, who was known for his love of material comforts.

‘No kingdom can sustain without means and resources,’ Babur addressed his men. ‘By the labours of several years, by encountering hardship, by long travel, by flinging myself and the army into battle, and by deadly slaughter, we, through God’s grace, have beaten these masses of enemies and taken their vast plains. Now why go back and stay in the harsh poverty of Kabul?’

He was ecstatic about suddenly changing from a dignified robber into a grand emperor, and felt that he must thank the Cosmic Power who had favoured him. With the zeal of an Albiruni he carried out an extensive research on India, studying its historic documents as well surveying its wildlife, revenues, peoples and resources. Then he wrote a complete treatise on this country and added it to his memoirs.

And it was at this time that Babur felt lonelier in life than he had ever been. Babur’s companions had completely failed to understand the change that had occurred in him after Panipat. They opposed him, arguing that the best course was to plunder India like Taimur had done, and carry its wealth back home. The lines Babur wrote at this point in his memoirs are charged with bitterness and dejection.

‘It’s true that they can’t be blamed just for wanting to go back, and this man (Babur) has enough sense to distinguish between honest opinion and mutiny. But how discourteous of them to tell a man that things should be done differently when he is seeing something as a purpose to be fulfilled and has reached his resolution!’

And just then, the mother of Ibrahim Lodhi attempted to assassinate Babur through poisoning. Babur survived the attempt, though it is thought that the poison left some impact on his system. But the emotional trauma was too great. Something in the old lady had reminded him of his dead mother, so that he had exalted her to the status of Queen Mother. Even after she had poisoned him, Babur didn’t have the heart to kill her and dispatched her to Kabul. Fearing a hostile reception there, she jumped into a river on the way and drowned.

‘Till now I had not really known what a sweet thing life could seem to be!’ Babur remarked in his letter about the incident. In the Battle of Kanwaha [or Khanwa], which followed soon afterwards, he killed the last known demons within him. His astrologer forecast that Mars, the planet of War is on the enemy’s side. Babur refused to listen to him and called upon God, who was in any case the only one who understood Babur anymore. Making a resolve never to drink alcohol again, Babur ordered the goblets to be broken and the metal distributed among the poor. Yet he was able to see a romance even in giving up wine, seeking his inspiration in a Persian verse, ‘Tauba hum bimaza neest, bichash!’ (Abstinence has its own savour, taste it!). But as he gained victory over the Hindu enemy Rana Sanga [Maharana Sangram Singh], he began seeing himself as a champion of Islam, though even that couldn’t prevent his visit to the temples of Gwalior. In his memoirs he describes them entirely from an artistic point of view and refrains from making any religious comment against idolatry. He didn’t order any harm to the idols.

There was one more lesson to learn. News arrived from Delhi that Humayun had broken into the treasury in his absence and opened up several of the boxes belonging to his father. ‘I had never looked for such a thing from him,’ Babur remarked in his memoirs. However, his love for Humayun didn’t diminish, and secretly he must have wondered about the divine significance of this incidence.

The story of Babur’s death is famous but few have bothered to explore the several layers of its mystical meaning. It is said that Humayun fell ill and physicians lost all hope of recovery. Babur was told that in India people sometimes offer their dearest possession to God and pray to Him to accept it as a substitute for the life of their dear one. He readily said that he would do so, and the nobles thought he would offer the Koh-i-Noor diamond. ‘I can’t offer God a stone!’ Babur said, and went on to pray that his own life be accepted as an offering. Humayun recovered miraculously and Babur grew ill day by day. He died on 26 December 1530.

We shall never know the dialogue Babur had with God on that fateful night because the last pages of Baburnameh have disappeared without trace. People have seen the incident as a proof of a father’s love for his son. But there is another layer of emotions involved in the incident. ‘Like flute, we too have two ends,’ Babur must have remembered from Rumi. ‘One is hidden between His lips, while the other, full of noise and life, is opened towards the world. But whoever can see, knows that the sound of this end is coming from the other one alone. The sound of the flute that is our soul is due only to His breath. The song of our soul is coming from Him alone.’

It is quite possible that just when love for his son tempted him to ask God to change His Divine Will, the romantic warrior suddenly recognized that if we have any claim over those whom we love then God too has claims over us. Is it possible that Babur, who had never stayed with a single moment of time once it was past, understood why his soul had shied away from the men and women he had wanted to love? It is quite possible that Babur at last recognized who his true Lover was, and prayed for an everlasting union. O Babur! Better seek to be happy, for the world is not to be again!

This article is part of the series “The Great Mughals” : Tamerlane | Babur | Khanzadeh Begum | Humayun | Akbar the Great | Anarkali | Jahangir | Nurjahan | Shahjahan | Mumtaz Mahal | Dara Shikoh | Aurangzeb Alamgir | Muhammad Shah “Rangeela”

This article is part of the series “The Great Mughals” : Tamerlane | Babur | Khanzadeh Begum | Humayun | Akbar the Great | Anarkali | Jahangir | Nurjahan | Shahjahan | Mumtaz Mahal | Dara Shikoh | Aurangzeb Alamgir | Muhammad Shah “Rangeela”

Next in the series: Khanzadeh Begum (‘At the Altar of Sacrifice’)

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]