In the previous posts of this series, we have considered some of the implications of how Iqbal and his school of thought, i.e. the All-India Muslim League, would have liked us to transform ourselves so that we might participate in the life of our communal self in a conscious manner. Let’s now consider the new outlook that results from this transformation.

Iqbal believed that the modern period in history started with the advent of Islam. This is when humanity, which had been passing through an age of minority until then and had been relying perpetually on the authority of prophets, finally came in possession of inductive reasoning.

It was at this stage that the Prophet of Islam appeared and delivered the Quran, the first and the only scripture to announce emphatically that there would be no further revelation binding on humanity, and that humanity from then on should be its own guide with the help of what had already been revealed (including all the revelations prior to the Quran).

Iqbal saw the revelation of the Quran as the beginning of a universal process in which many cultures are consciously or unconsciously working out the infinite implications of this message, regardless of how they feel about the Muslims and possibly even if they did not have much of a direct contact with Islam:

Take it from me that the religion of Islam is an imperceptible and unfeelable biologico-psychological activity which is capable of influencing the thoughts and actions of mankind without any missionary effort.

Iqbal, “Islam and Nationalism” (1938)

One example quoted by Iqbal is the great movement that transformed Europe between 1650 and 1850, and is known as the Enlightenment. Iqbal saw it as the coming of age of the modern Western culture. This is when solidarity, equality and freedom were adopted as the ideal principles. It was also realized that politics should be motivated by the desire to seek consensus, because a natural law governs the affairs of human soul and the existence of a collective ego is therefore possible. It was also believed that there could be perpetual peace in the world, so that no nation oppresses or exploits another.

It is true that in the middle of this process, Europe also began to develop an extremely ruthless kind of imperialism, and the European colonialists spread out into the world for exploiting the weaker nations. The present-day academia often attempts to discredit the Enlightenment by citing the case of European imperialism, but the representatives of the South Asian Muslim Renaissance have always treated those two currents of the modern Western culture as separate from each other, each striving to cancel out the effect of the other (“Two red lines crossing each other,” to quote the character Ali Imran from one of the novels of Ibn-e-Safi).

From this point of view, it is quite significant that many of the radical writers of Enlightenment had admitted that their ideas were either derived from the original message of the Quran or were at least compatible with it.

Similar ideas were being presented in the world of Islam even at that time (as suggested by Iqbal in his paper “Islam and Ahmadism” in 1936, and now acknowledged independently by such academics as Anthony Black of the University of Edinburgh and the journalist Christopher de Bellaigue). Yet, the big difference was that in Europe, many of those ideas got implemented whereas in the Muslim countries they remained mere dreams at that time.

Things began to change some time after 1850. As we have seen in the previous episodes, a national renaissance occurred among the Muslims of India after 1858, later initiating a unique process of collective evolution that is still going on. Other Muslim countries also experienced their own kind of awakenings between the early 1850 and 1950.

On the authority of Iqbal, we should see these movements of the Muslim world as a continuation of European Enlightenment, which itself had been admittedly inspired from the Quran:

The most remarkable phenomenon of modern history, however, is the enormous rapidity with which the world of Islam is spiritually moving towards the West. There is nothing wrong in this movement, for European culture, on its intellectual side, is only a further development of some of the most important phases of the culture of Islam.

Iqbal, “The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam” (1930-34)

The Muslim Renaissance of South Asia and the work of the All-India Muslim League, discussed in some detail in the previous episodes, were in turn “further development” of some of the most important ideas of European Enlightenment of the previous centuries. Iqbal attested that the essence of Tauhid as a working idea is solidarity, equality and freedom, and that the mission of the Prophet of Islam was to universalize these ideal principles. The Enlightenment ideal of consensus-based politics became realized in the form of a national organization, and the natural law of human soul which the writers of European Enlightenment had so eagerly sought to discover was explained by Iqbal, perhaps conclusively, as his philosophy of ego (“khudi”) and his four basic postulates about human condition. The possibility of perpetual peace in the world was also, according to by both the Quaid-i-Azam and Liaquat Ali Khan, an important implication of the idea of Pakistan.

But possibly the most significant was the fact that the Indian Muslims succeeded in forming a national organization, the great dream of true democracy which had remained unfulfilled in the West (as explained in the third episode).

Pakistan, therefore, is a child of the same current of Enlightenment which had manifested in Europe in the eighteenth century, and which reached a new high in the Muslim world, especially the Muslim India, in the twentieth.

“The Story of Pakistan, its struggle and its achievement, is the very story of great human ideals, struggling to survive in the face of great odds and difficulties.”

Jinnah, address to the people of Chittagong, 23 March 1948

The situation had reversed from what it had been two hundred years ago. The ideals of Enlightenment such as freedom, equality and solidarity were animating the political life in the countries of Islam in the first half of the 20th Century, while Europe was now unable to live up to those ideals due to its imperialism.

Also, the writers of European Enlightenment in the 18th Century had known more about contemporary Islam than their like-minded Muslim contemporaries knew about contemporary West (compare Rousseau with Shah Waliullah, for instance). But now, the Muslim writers knew more about their like-minded Western contemporaries than the latter knew about them. Consider, for instance, that Iqbal quoted a very large number of contemporary Western authorities in his writings (especially The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam) but hardly any of them gave him a “pingback” in their work.

All these were signs that the tables had turned, and it had now fallen upon Islam to guide the West in the course of Enlightenment. This is what Iqbal stated most eloquently in 1923, in his Urdu poem “The Dawn of Islam” and the preface to his Persian anthology The Message of the East (published the same year). A little later, he declared:

The idealism of Europe never became a living factor in her life, and the result is a perverted ego seeking itself through mutually intolerant democracies whose sole function is to exploit the poor in the interest of the rich. Believe me, Europe today is the greatest hindrance in the way of man’s ethical advancement. The Muslim, on the other hand, is in possession of these ultimate ideas on the basis of a revelation … for which even the least enlightened man among us can easily lay down his life …

Iqbal, “The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam” (1930-34)

How we came to lose sight of this continuity of Enlightenment from the advent of Islam to the 17th Century Europe and then back to the 20th Century Islam is a matter which I hope to explain elsewhere. It should be clear in any case that if we had not stopped seeing this continuity, we would have noticed “the seven stages of Pakistan” long ago, and understood them for what they are.

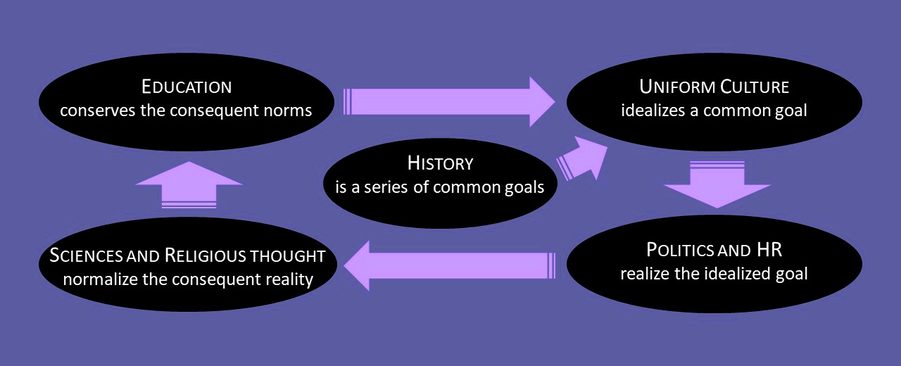

By looking at them in the light of the Enlightenment ideas (of both the European and the Muslim currents), we can see that our society has been working, internally, in the following manner:

In simple words:

- History is a series of goals commonly adopted and possibly achieved. This is completely consistent with the Enlightenment view of human being, especially the ideas of Rousseau and Iqbal. Rousseau believed that the essential nature of human being consists in will, and Iqbal developed the idea further to suggest that human soul is an ego, whose life consists of conceiving and realizing a series of goals. Since both these thinkers believed in a communal self (the general will according to Rousseau, and the collective ego according to Iqbal), it should follow that a true nation must also be a communal self, and just like an individual self, the life of this communal self must also comprise of a series of goals. This is also close to how the Enlightenment thinkers generally perceived history, contrary to the existing pessimism.

- Uniform culture idealizes the above-mentioned goals that have been commonly adopted, and thus it makes us aware of those goals. This is because the representatives of this type of art and literature, unlike the priests of high and popular cultures, receive intuition directly from the communal self or the collective ego of their nations. This phenomenon, clearly observable in the seven stages of Pakistan, again corroborates the views of Rousseau and Iqbal on the subject. Again, it is consistent with the Enlightenment view of art and literature, and contrary to what the priests of high and popular cultures would like us to believe today.

- Politics and human resource cannot do anything more than realizing a goal that has already been idealized in art and literature. In the seven stages of Pakistan, we see that politicians and administrators could not and did not choose the goals that were eventually achieved. Just as Iqbal had said, “Nations are born in the hearts of poets; they prosper and die in the hands of politicians.” (Stray Reflections, p. 112). Politicians and administrators in our history have only been instruments through whom the goals already idealized in the uniform culture have been achieved, knowingly or unknowingly. Jinnah is the best example of a political leader who was aware of this, and most of those who came after 1954 belong to the other category.

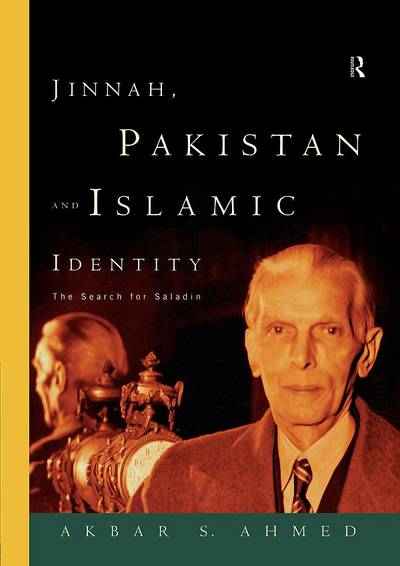

“Jinnah … not only embraced Iqbal’s political philosophy but consciously absorbed his conceptual framework. Now he was at one with the poet and through him with the powerful mainstream of Muslim thought and culture.”

Akbar S. Ahmed

- Sciences, religious thought, philosophy and any other means through which we may seek the truths about our society can only help us adopt to the changes that have already occurred as a consequence of the political and social actions described above (but the term “religious thought” is being used here only as a subset of religion, and not in the sense of religion itself because the latter could actually include all other domains as well). Just in the previous post, we have seen that the most significant change that has occurred in our society, thanks to the Delhi Resolution in 1946, is that we have become capable of “conscious evolution”. If we take this to mean that we have discovered the collective ego as force of Nature, we can see that Iqbal was right when he said in 1930, “the day is not far off when Religion and Science may discover hitherto unsuspected mutual harmonies.”

- Education truly means to pass on the above-mentioned outcome to the next generations. Contrary to what we think, education is not merely the acquisition of fashionable aphorisms. “Knowledge for the sake of knowledge is the maxim of the fools,” said Iqbal. Education should now be understood to mean the capability of “conscious evolution.”

If the above-mentioned domains of knowledge are redefined in this manner for our next generations, the outcome cannot be anything except a return to the concept of “national organization“. This would be thoroughly consistent with the vision of Jinnah, who had offered the following advice to the youth some time after the birth of Pakistan:

My young friends, I would, therefore, like to tell you a few points about which you should be vigilant and beware. Firstly, beware of the fifth columnists [traitors and foreign agents] among ourselves. Secondly, guard against and weed out selfish people who only wish to exploit you so that they may swim. Thirdly, learn to judge who are really true and really honest and un-selfish servants of the State who wish to serve the people with heart and soul, and support them.

Fourthly, consolidate the Muslim League Party, which will serve and build up a really and truly great and glorious Pakistan. Fifthly, the Muslim League has won and established Pakistan and it is the Muslim League whose duty it is now, as custodian of the sacred trust, to construct Pakistan. Sixthly, there may be many who did not lift their fingers to help us in our struggle – nay, even opposed us and put obstacle in our great struggle openly, and not a few worked in our enemy’s camp against us – who may now come forward and put their own attractive slogans, catch-words, ideals and programs before you. But they have yet to prove their bonafides – or that there has really been an honest change of heart in them – by supporting and joining the League and working and pressing their views within the League Party organization, and not by starting mushroom parties, at this juncture of very great and grave emergency when you know that we are facing external dangers and are called upon to deal with internal complex problems of a far-reaching character affecting the future of seventy millions of people. All this demands complete solidarity, unity and discipline. I assure you, “Divided you fall. United you stand”.

Jinnah, Speech at the Dhaka University Convocation, 24 March 1948

Before proceeding further, I would like to clarify that the parties called “Muslim League” today might or might not have descended from the original one. Whatever is being said about the “Muslim League” here is strictly about the original organization, and need not be applied to its present-day namesakes.

We can see that the idea of national organization was emphasized in three out of the six points which Jinnah gave to the youth. This should not surprise us if remember that the All-India Muslim League was itself the natural and effortless outcome of an educational movement:

And it was not without significance that fairly prominent among the founders of the Muslim League at Dacca at the end of 1906 were some alumni of Syed Ahmad Khan’s own College.

Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar, Presidential Address delivered at the Indian National Congress at Cocanada, 26 December 1923

In the second post of this series, we saw that the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent pledged loyalty to the national organization at the time of adopting the Delhi Resolution in April 1946, which led to the creation of Pakistan. Also, the revival of this organization appears to be imminent in the near future. In the third post, we saw that it has been a recurring dream in our art and literature, and in the fourth we saw that it is the practical implication of the fundamental principle of Muslim constitutional theory. In the fifth post, we saw that it can give us a society free from fear and want. In this post, we have seen that it has been possibly our greatest contribution to modern civilization.

We may now conclude that it has to begin with education, just as it did in the past. Sir Syed introduced a certain type of education and the national organization emerged naturally as a result of that education – as naturally as a medical student becomes a medical practitioner after the completion of medical studies, or a student of engineer becomes an engineer after studying engineering.

It took them twenty or thirty years. They were starting from the scratch – sowing the seed in wilderness, or prospecting for a resource in a ground that had never been explored before. We would not be starting from the scratch. We would not be sowing the seed but simply wanting to gather the fruits of the previous efforts of our ancestors. We would not be prospecting uncharted territories but only seeking to tap the resources which the birth of Pakistan has already brought to surface but which have remained untapped for long. So, if it took the pioneers some twenty or thirty years, it may take us only twenty or thirty months, or twenty or thirty weeks, or twenty or thirty days – who knows!

Indeed “Education is the passport to the future”.