In the previous post of this series, we saw that the Muslim society of South Asia has a collective ego, or a communal self. Since 1887, this communal self has been manifesting itself by adopting and achieving consecutive goals of its own. The goals get achieved regardless of our awareness, but we can benefit from them only if we choose to participate in the process.

For this, we need to transform ourselves internally as well as externally:

In order to participate in the life of the communal self, the individual mind must undergo a complete transformation, and this transformation is secured, externally by the institutions of Islam [law and government], and internally by that uniform culture which the intellectual energy of our forefathers has produced.

Iqbal, ‘The Muslim Community – A Sociological Study’ (1911)

By internal transformation is meant a change in our habits of thought, and that is the topic of this post. The term “culture” is used here in its broadest sense to include everything produced by the intellectual energy of a people – art, literature, scientific achievements and so on. It can transform us “internally” when it shapes or influences our habits of thought. However, a culture may or may not be “uniform”, and Iqbal is recommending only the uniform one.

The uniformity of a culture can be of two types: across countries or within a country. Let’s consider both.

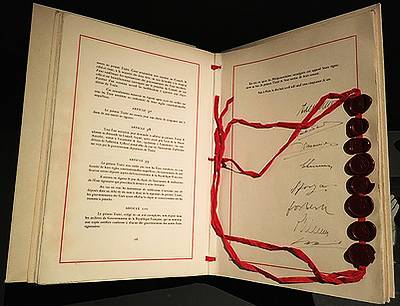

The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1951 and now seen as the basis of the European Union, mentions “the contribution which an organized and vital Europe can bring to civilization.”

This is an example of the uniformity of a culture across countries – a common European culture that could be offered to the world.

Iqbal saw the art, literature and scientific achievements of the Muslims of the past in the same way. They had been, or could be, shared by all Muslims of the world because they originated from the powerful impact of the Prophet of Islam on the successive generations of his followers (a point explained by Iqbal in greater detail in his lecture, “The Spirit of the Muslim Culture”, included in The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam).

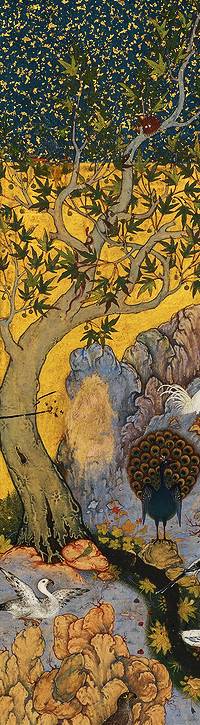

An example of such literature is The Conference of the Birds, an epic poem written in Persian by the great Sufi master Sheikh Fariduddin Attar around 1187.

In this poem, the birds of the world set out in search of their king, Simorgh, whom they have never seen before. They pass through seven valleys, facing a unique challenge in each. Many perish on the way, and only thirty make it to the palace. There, they realize that they are collectively the Simorgh (literally meanig “Thirdy-Birds” in Persian). In spite of becoming a part of the whole in this manner, each bird still retains its unique individuality.

A process of gradual evolution through which individual members and units transform into a real whole without losing their uniqueness, as seen in this story, is how Iqbal saw the life of the global Muslim community over the centuries that had passed before him, and the times that were coming. This is the theme of this story, and hence a mind transformed by this story can better participate in the life of the global Muslim community.

But such a mind will be better equipped for participating in the communal self of the South Asian Islam as well (or the collective ego of Pakistan, for that matter). This is because the history of this community, at least since 1887, appears to be driven by the same process that is the subject of Attar’s story. This is what we have seen in the previous episode.

Also, the political ideal of this community was envisioned by Iqbal in terms no different than the outcome of the journey described by Attar. Consider, for instance, the following lines which conclude the famous presidential address delivered by Iqbal at the Allahabad session of the All-India Muslim League in 1930:

Why cannot you who, as a people, can well claim to be the first practical exponent of this superb conception of humanity, live and move and have your being as a single individual? I do not mystify anybody when I say that things in India are not what they appear to be. The meaning of this, however, will dawn upon you only when you have achieved a real collective ego to look at them. In the words of the Quran, ‘Hold fast to yourself; no one who erreth can hurt you, provided you are well-guided.’” (5:105)

Iqbal, “The Allahabad Address” (1930)

If our history is following a course of its own as seen in the previous post, it is likely to converge on the kind of political life described by Iqbal in these lines. The type of culture represented by Attar, i.e. the Muslim culture of the previous centuries that has been “uniform” across the world of Islam, can prepare our minds for such an outcome, and thus enable us to participate in this process.

There is also a remarkable similarity between the seven valleys described by Attar and the seven stages of our history discussed in the previous post, but we can leave that for some other occasion.

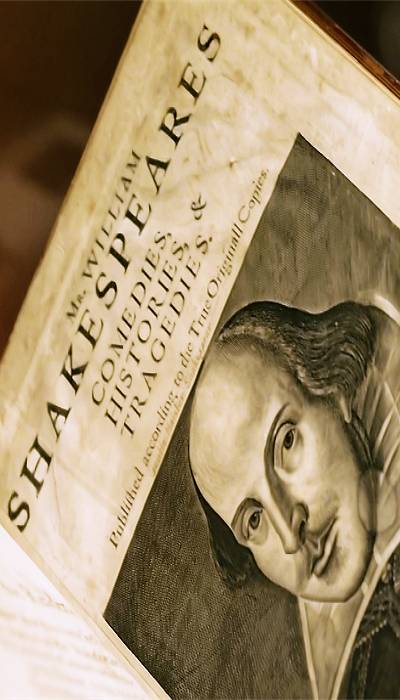

The other type of uniform culture is that which has been enjoyed equally by the high and the low at least at some point in the history of a people, e.g. the plays of William Shakespeare when they were first produced in England, or the poetry of Iqbal when it was first presented in the Indian sub-continent. It would be wrong to call such art and literature either “high culture” or “popular culture”. It belongs to a category of its own, which might be called “consensus culture”, i.e. a type of culture which is uniform within a country or region.

From this point of view, an indispensable part of our uniform culture is the literature of the All-India Muslim League from 1906 till 1947, and of its Pakistani successor organization up to 1954. Its resolutions, proceedings and presidential addresses are the combined deliberations of the best minds of the South Asian Muslim society over a period of almost five decades.

Before proceeding further, I would like to clarify that the parties called “Muslim League” today might or might not have descended from the original one. Whatever is being said about the “Muslim League” here is strictly about the original organization, and need not be applied to its present-day namesakes.

One of the most important aspects of the literature of the original Muslim League is the process through which the leaders came to be led by the masses. This is a refutation of that “aristocratic radicalism”, or the top-down approach, which has been shaping our habits of thought since 1954. The aforementioned literature of the Muslim League shows us how ideas were being produced collectively at the grassroots level and moving up, rather than the other way around.

To facilitate this bottom-to-top thinking was one of the main objectives of the great movement started by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, which Jinnah later called “the National Renaissance of the Muslim India”. The Muslim League was a child of that movement.

Once we are able to start thinking in this way, we might also see the significance of the fact that the most popular writer at each stage in our journey was always popular across the society – among the high and the low, among the modern and the conservatives, and so on.

The work of such writers and their associates obviously forms the modern and contemporary part of that uniform culture through which our internal transformation is to happen. Each of these writers idealized the goal which the collective ego was pursuing at that stage, and offered acceptable solutions for achieving that goal. Those solutions are still relevant if we want to bring unity to our society. Here is the list of the writers from the first six stages:

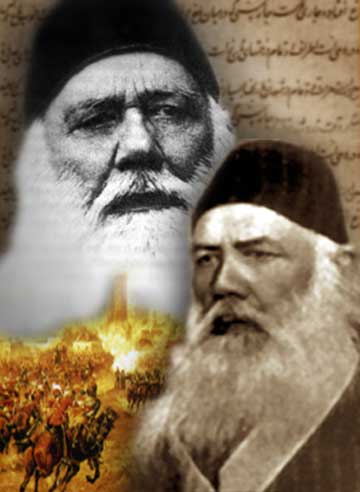

- Stage 1, 1887-1906: Sir Syed Ahmad Khan

- Stage 2, 1907-1926: Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar

- Stage 3, 1927-1946: Allama Dr. Sir Muhammad Iqbal

- Stage 4, 1947-1966: Ibn-e-Safi

- Stage 5, 1967-1986: Waheed Murad

- Stage 6, 1987-2006: Mustansar Husain Tarar

The first three names in the list have always been recognized as closely associated with the Muslim Renaissance. We may now see the latter three as legitimate successors of the same movement. Out of them, I have tried to highlight the messages of Ibn-e-Safi in a trilogy of heavily annotated excerpts from his works in Urdu, Psycho Mansion (2011), Rana Palace (2011) and Danish Manzil (2017). For a quick reference, please check my blog post in Urdu, “Aazadi kay baad“. Further information about him can be found at his official website.

On Waheed Murad, you may consult his biography written by me, Waheed Murad: His Life and Our Times (2015). For a quick reference, see my posts “The mystery behind Waheed Murad“, “Samandar: a parable” or “Khudi, for those who want it.” You may also like to see the excellent piece written about him by the Bangladeshi-Australian writer Mehreen Ahmed, “Emotion recollected in tranquility“. Further information about him can be found at the website which I maintain about him.

The work of Mustansar Husain Tarar has already been appreciated highly from other points of view. Its relevance to our uniform culture is something which I hope to discuss elsewhere.

There is a long list of artists and writers closely associated with the ones named above, but even the following two examples might suffice for showing the inherent unity in our uniform culture.

The national anthem – the nucleus of the uniform culture produced after the birth of Pakistan – was written by Hafeez Jallundhri, who happened to be among the disciples of Iqbal, the third and the most highly acclaimed of the six personalities named above.

The two national songs that have by consensus acquired the highest stature after the national anthem are “Sohni Dharti” by Masroor Anwar and “Jeevay Pakistan” by Jamiluddin Aali. The first of these two poets was a member of the team of Waheed Murad, the fifth personality in the above list. The music for both songs was composed by Sohail Rana, who was also closely associated with Waheed and has acknowledged him as “mentor”.

While listening to “Jeevay Pakistan”, we can easily see a reinterpretation of Simorgh as a metaphor for Pakistan (whether or not intended by the poet). If you like, please watch the video embedded below and note how everything said about Pakistan in the three stanzas of the song is equally true of Simorgh as depicted by Attar.

The seventh stage, which has started in 2007, is an age where almost every individual is an author or producer of culture in some sense, thanks to the social media. A tweet, a video, an image or a post from a novice can go viral and far surpass the outreach of the most popular writers of the previous periods at least temporarily.

Among this enormous output, the contribution of the educated minds often represents nothing more than those divisive modes of thinking which have been formed under alien influences. But the contribution of the unschooled mind is often very different, and there is one example which I want to share in particular.

Nobody among us can forget the tragedy of 16 December 2014, when 149 people, including 132 children, got killed in the Army Public School Peshawar. Many of us expressed our grief. One of those expressions came from a Pakistani truck driver working abroad.

While watching the video which he shared through social media (embedded below), please answer this question: Is this message consistent with the message given by Attar as discussed in this post, and with the message given by Iqbal in the concluding lines of his Allahabad Address quoted earlier?

This video is a sample of that “uniform culture” which is being produced among us, and through which our habits of thought should be reformed in order to participate in the life of our communal self, or the collective ego. I hope that the video will also help us come out of our fantasies of aristocratic radicalism, and open our eyes so that we may see that the masses no longer need to be told by their leaders, or by us, what they should do. They are fit to participate in the process of decision-making as equals.

As already mentioned, this is the most important change which we need to bring to our habits of thought in order to participate in the life of our communal self.

But why should we participate in the life of the communal self, and what will such participation give us? As we have already seen in the previous post, our participation in the life of the communal self will ensure that we are at an advantage rather than loss when this communal self achieves its present goal.

We have already seen that this goal is the elimination of those factors that stand in the way of a revival of the “national organization” which had founded Pakistan. The essence of our uniform culture, including such specimens as this message from the truck driver, has remained consistently the same as the essence of that organization. Hence, it can very well prepare us for what awaits us almost certainly in the near future. This is what is meant by changing our habits of thought in order to participate in the life of the communal self.

However, a mere change in the way of thinking cannot be sufficient unless it is accompanied by a change in action and behaviour. In the next post, we will look at the advice which Iqbal has given us in that regard.

The untold story of Pakistan | The seven stages of Pakistan | The uniform culture | National organization | Conscious evolution | National education

Well said. A uniform culture is what we need. Such as equality, no black has a preference on white, and so on. But too bad that everyone considers themselves better than others!

There are two comments here.

The correlation between Attar’s epic poem’s narrative with the specific stages of the history of South Asian Muslims as perceived by you, in your research is a very interesting idea. It would be nice for readers to see how you see his correlation; and what can be derived from such a reading. Perhaps another post can be developed to discuss this topic in more detail.

Secondly, the video by the truck driver is especially moving. It is heart wrenching! Furthermore, it also becomes a very strong argument supporting the fruit of your overall hermeneutics. It should now offer, through its own example, a method for your readers to search for such ways of thinking in the larger community – from children, to speakers of multiple languages, labour of various professions, etc.

The truck driver who spent two hours driving in the dark of the night, where he could lighten his heart and share his raw and unpretentious emotions with the world – this was me a few days ago – unable to carry the pain of what some self-centered elites are doing with this country. I never thought I would relate to a truck driver but at this point he is my new-found brother-in-pain. The context may change but the pain becomes a part of us. It could weaken us or it could make us stronger and more resilient. The fight is amongst the powerful but really its the common man who is suffering – not just the physical anguish of losing loved ones in these vulgar incidents of hatred and terrorism but the pain that finds a permanent abode in our heart. We are all suffering, in one or the other, and we are all more similar than we think – the rich and the poor, the educated and the uneducated. This truck driver was able to give a solution that most intellectuals have forgotten – to bring all the Muslims together in a conference of sorts and to unify based on the real roots of this Ummah – the Quran and The Prophet (SAWS) and discuss the solution to our problems and stop this senseless bloodbath. Will the real Pakistanis, please stand up!

“Love without power is sorcery,

Love with power is prophecy”

Thank you for this post. Literature has always shaped the societies. It’s subtleties enable us to enjoy life’s burdens, providing us with strength to move on. We have forgotten our ways. I remember once you mentioned how people used to read Ibne Safi’s novels diligently. How Waheed Murad was copied by poor and rich alike. How he touched many lives and shaped our thoughts. Indeed these people are prophesiers. As you have said, we need to change our habits to understand the power of Literature and participate in the life of the communal self. There is a literature outside the dichotomy of high and low.