1858 – 1886: background and the early years

In 1858, India came directly under the British Crown, and the proclamation of Queen Victoria became a magna carta for its people (Iqbal wrote an elegy on her death in 1901, while the founder of Pakistan called her “a good and noble queen” on the eve of independence in 1947). Unlike the post-1927 Hindu leadership, Iqbal’s school of thought retained a very high regard for the British as a nation (Iqbal’s writings on the subject pre-empted in great detail the official statement issued by the founder of Pakistan in 1948, “There is, I believe, a good measure of fellow-feeling between Muslims and the British people. It comes, perhaps, from a practical way of thinking and an aversion from mere theorizing and sentiment. There are, of course, rubs and difficulties and misunderstanding now and then; but these are not so important as the friendship”).

In 1863, Syed Ahmad Khan (later Sir) started social reform in British India on the basis of the Sufi paradigm of love, where love for an individual and love for one’s own community are steps towards the love of humankind, nature and universe. The movement resulted in the establishing of a college at Aligarh in 1877, a chain of ‘Islamia’ schools throughout the country, and the formation of Mohammedan Educational Conference in 1886.

The birth of the Confederation of Canada in 1867, although not mentioned by Iqbal directly, was possibly one of the most important developments of the Nineteenth Century from his point of view: it eventually led to the idea of commonwealth, and his school of thought defined its struggle essentially as participation in the task of achieving a British Commonwealth of independent nations, while at the same time seeking to establish other similar families of states, especially one of free Muslim countries.

Iqbal was born in Sialkot in British India to Sheikh Nur Muhammad and Imam Bibi, both of Kashmiri origin. He had five siblings (not counting a brother, who reportedly died in infancy). The date and year of his birth are disputed but the most commonly accepted are 3 Zulqida 1294 AH, corresponding to 9 November 1877 (apparently he miscalculated, and usually cited his year of birth as 1876).

His birthplace (pictured here), is now a national heritage building.

In 1886, one of the most revered Indian leaders of the age, Dadabhai Nauroji, contested election in England. Although an outspoken advocate of India against its colonial rulers, he declared to his British voters, “Standing as I do here, to represent the 250,000,000 of your fellow subjects in India … if I am returned by you, my first duty will be to consult completely and fully the interest of my constituents. I do not want at present to plead the cause of India.” Among his supporters was the living legend, Florence Nightingale. The common interests of Europe and Asia, and of Islam, later became a recurrent theme in the writings of Iqbal in spite of his harsh criticism of European imperialism.

1887-1906: a phase of inquiry

In 1891, Iqbal passed the Middle High Examination (8th Grade) held by Punjab University, as a candidate from Scotch Mission School Sialkot. Subsequently he passed Entrance (10th Grade) in 1893 as a candidate from the same school and F.A. (12th Grade) in 1895 as a candidate from Scotch Mission College (now Murray College), Sialkot. He passed B.A. (graduation) from Government College Lahore in 1897, and M.A. (masters) from the same in 1899. In 1907, he graduated again from Trinity College Cambridge (pictured here), and got doctorate in Arabic from Munich University the same year.

Maulvi Syed Mir Hasan (later Shamsul Ulema), his teacher at Sialkot, was a major influence on his mind while growing up. Hasan was an ardent follower of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and an active member of Mohammedan Educational Conference.

In 1893, Iqbal got married to Karim Bibi (pictured here in her old age, in the 1940s). She belonged to a prestigious Kashmiri family settled in Gujarat (Punjab), and the marriage was arranged by the elders much against Iqbal’s inclination. It eventually resulted in separation, though many years after the birth of a daughter Miraj Bano (1896-1914) and a son Aftab Iqbal (1898-1979).

Thomas Arnold (later Sir) was Iqbal’s teacher of philosophy at Government College Lahore in 1898 and 1899. He remained his mentor till 1908. He was also closely associated with the activities of Sir Syed and had taught at MAO College, Aligarh, before coming to Lahore.

Although he had mastered the classical skills of verse-making in Urdu and Persian at a young age, there is no evidence to suggest that he showed enthusiasm for participating in extra-curricular literary activities in his student days, i.e. up to 1899. The few exceptions include his earliest known published poem, from a magazine in 1893, and a memorable debut at a poetry recital organized by the Hakeem family in Lahore (later a pioneer of the film industry of Pakistan). Shown here is his earliest known photograph, believed to have been taken in the late 1890s.

In 1898, Iqbal sought a degree in law but failed in Jurisprudence. In 1901, he got disqualified from public service examination on medical grounds (apparently due to his defective right eye). In 1905, he got enrolled at Lincoln’s Inn, London (pictured here), and was called to Bar in 1908.

In the meanwhile, he retained a fellowship in Arabic at University Oriental College, Lahore, from 1899 to 1903, and was an assistant professor at Government College, Lahore, from 1904 to 1908 (later returning for two short stints as a professor in 1909 and 1918). In 1907 and 1908, he also taught Arabic at the University of London. He remained an examiner for various universities and a member of the senate of the Punjab University for most of his active life.

In 1899, he joined Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam, Lahore, a philanthropic organization dedicated to the welfare of Muslim orphans and the establishing of educational institutions. He retained his connection with this organization throughout his active life, sometime serving as president. His poetry recitals became a hallmark of the annual sessions from 1900 onward, and he also delivered extensive lectures on some of these occasions. He is also said to have taught for a few months in 1901 at Islamia College, Lahore (pictured here), which was being run by the Anjuman.

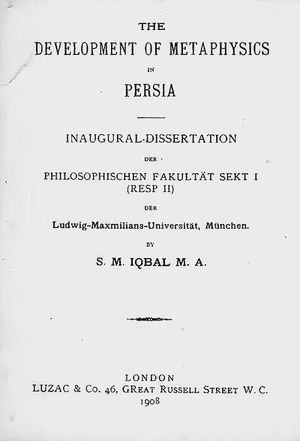

In 1900, he got his first research paper published in the Indian Antiquary, Bombay. It became a foundation for The Development of Metaphysics in Persia, the ground-breaking research that served as his graduation thesis at Cambridge and, with revisions, as the doctoral thesis at Munich, and published by Luzac & Co., London in 1908. Social sciences received more of his attention generally, but he continued to revisit metaphysics intermittently, most famously in the series of lectures collectively published as The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam by Oxford University Press, London, in 1934.

In 1901, his poems began to appear in Makhzan, a popular monthly magazine published from Lahore. They represent the earliest of his poetry to be anthologized by him ever – including the one that starts with the now iconic line, ‘Saray jahan se acchha Hindustan hamara’ (our India is better than the whole world). It became an unofficial national anthem for the Indians soon after its first appearance in 1904, and retains that place to this date. He also contributed a few essays to this magazine. One of them, ‘National Life’, appeared simultaneously with the patriotic poem, and treated the Indian Muslims as a separate nation.

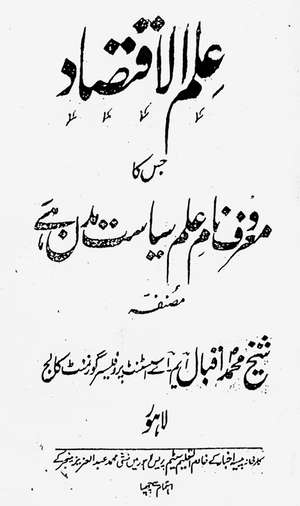

In 1904, he published Political Economy, his first complete book in prose, in Urdu. A compilation of current ideas in simple language, it also offered possibly the first hint of his lifelong mission: “A question has arisen in this age, viz., is poverty an unavoidable element in the scheme of things? Can it not happen that the heartrending sobbing of a suffering humanity in the back alleys of our streets be gone forever and the horrendous picture of devastating poverty wiped out from the face of the earth?” The answer, according to him, was that absolute freedom from fear and want could be achieved by developing the innate potential of human beings – the vision that eventually became “Marghdeen“, in a publication of 1932.

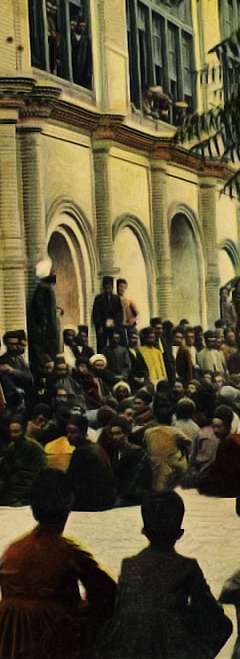

1906 was a watershed year: following a revolution (pictured here), Iran adopted a constitution and held election for the first time in its history. Over the next few years, other Muslim countries also adopted radical measures for moving towards democracy. In British India, the Muslims founded their first political organization, All-India Muslim League, in December 1906. It was a unique experiment because the party was open to any school of thought that could gain majority (it offers perhaps the only case study of what the American social scientist Mary Parker Follett would later describe as a “group organization”). The immediate goal of the Muslim League was separate electorate, i.e. the right of the Muslim minority to elect its own representatives to legislative councils or assemblies. Iqbal, residing in England from 1905 to 1908 (and in Germany for a few months in 1907), understood these developments to be a rediscovery of Islam’s own original ideals under the pressure of European influence.

1907-1926: the discovery

Iqbal marked the year 1907 as the beginning of a new phase: he announced his mission in a poem titled ‘March 1907’, and went on to deliver a complete conceptual framework of social science in two research papers and a lecture, presented respectively in 1908, 1909 and 1911.

He defined human nature as essentially consisting in will, not intellect or understanding, and ethically good. Locating the ultimate source of evil in fear, he defined salvation as absolute freedom from fear and grief, and declared it possible even in this world.

He claimed that this worldview, originally Quranic, was also the basis of modern Western civilization, although both societies are structured differently.

The structure of the Muslim community, according to him, consisted of faith, uniform culture (art and letters that have been equally appreciated by the high and the low), and common institutions (law and politics). The ideal of Islam in the present age was to produce (a) individuals who held fast to their own cherished traditions while assimilating all that might be positive in other cultures; and (b) a new world suitable for such individuals.

While visiting Germany in 1907, Iqbal fell in love with Emma Wegenast (pictured here), a tutor of the German language, but could not marry her due to opposition from her family. Although they could never meet again, his extant letters to her suggest that she was always his muse afterwards, and he remained mentally in Europe even after returning to India. Since he was practically separated from his first wife, he remarried in Lahore in 1910, but some misunderstanding prevented the marriage from being consummated at that time, and he took a third wife in 1913. An unexpected resolution of the earlier misunderstanding about the second wife compelled him to take her too (although in principle he was in favour of monogamy). She, Sirdar, gave birth to a son Javid (1924-2015) and a daughter Munira (b.1930), and died in 1935. The third wife, Mukhtar, died issueless in 1924.

In 1915, Iqbal published a long poem in Persian, which became his first book of poetry after a second part was added to it a few years later. In all, he published nine books in verse – some Persian, some Urdu, and the last one published posthumously containing verses in both languages. They offer the reader an opportunity to engage emotionally with the conceptual framework proposed by him earlier in prose. The keyword in his poetry is ‘khudi’ – the Persian for self or ego. Through it, he redefined soul redefined as ‘a directive energy’, i.e. an energy that can set its own direction unlike heat, electricity and other known forms of energy.

In 1919, a new constitution was implemented in India, introducing general election for the first time in the country but without transferring any real authority to the elected representatives. Iqbal believed that it created (a) a class of influential but selfish elite, who consolidated their hold on the society with the help of (b) an equally selfish class of native bureaucrats and careerists. He started a lifelong struggle against both these classes, while declaring that the British had given up their earlier policy of promoting democracy in India. ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi launched a short-lived, unsuccessful but much-hyped campaign against the same constitution in 1920. Iqbal praised Gandhi initially but soon became disillusioned, and later described him as a hypocrite – a double agent serving the interests of foreign imperialism as well as local capitalism.

In 1920, the first of the long Persian poems of Iqbal was published in an English translation by McMillan, London, and received mixed reviews from critics including E.M. Forster. In 1922 came out the first monograph about him, A Voice from the East, written by a friend. His phenomenal popularity (which had by then surpassed any other Indian Muslim poet alive) was explained as resulting from the fact that the collective evolution of the society – the masses as well as the elite – required a poet-philosopher at that particular point when he made his debut.

In 1922, the Bengali Hindu visionary C. R. Das presided over the Indian National Congress. Quoting extensively from the work of the American management scientist Mary Parker Follett, he proposed a unique programme for achieving self-government in India: (a) reassure minorities; (b) fight election on one-point agenda of self-government; (c) gain unanimous support of the entire nation; and (d) implement non-cooperation from within the assembly. He believed that as a result of these steps, (e) the British will yield. Iqbal called this a political interpretation of the spiritual principle of ‘khudi’, which he had expounded in his Persian poems. The Congress rejected the proposal, and Das died in 1925. Fifteen years later, and two years after the death of Iqbal, Muslim League would start implementing the same programme and would liberate India within seven years.

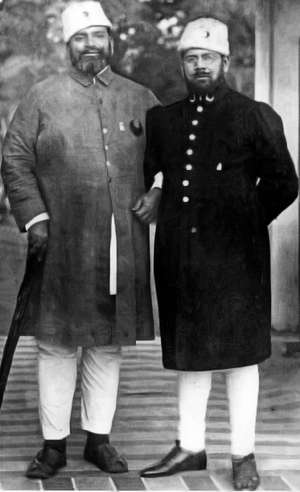

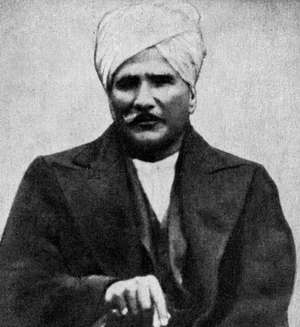

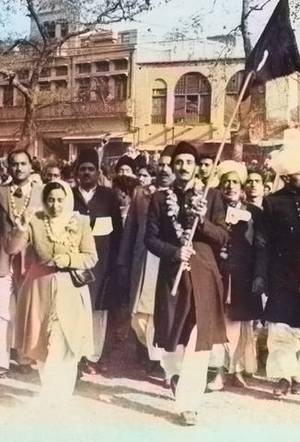

In the early 1920s, the Indian Muslims launched the Khilafat Movement against the British rulers, demanding the freedom of Turkey and the Middle East. The stars of this movement were Iqbal’s close friends, Muhammad Ali Jauhar and his brother Shaukat Ali (pictured here from right to left). Turkey eventually won its freedom and delegated the role of the caliph to the elected assembly instead of an individual. It also gave up the age-old dream of bringing the entire Muslim world under a central authority, and supported the concept of independent Muslim states coming together like a family. Iqbal voiced his support for both these radical measures.

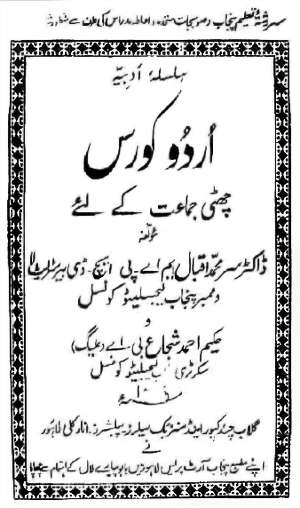

In 1924, Iqbal and his protégé Hakeem Ahmad Shuja produced a series of Urdu textbooks for grades 6, 7 & 8, and a few years later they added another textbook for grade 5 to the series. The series became immensely popular and remained in schools till the early 1950s (since 2015, it has been relaunched in a heavily revised and updated version, Kitab-e-Urdu). Iqbal also produced a textbook of Persian literature, Aina-i-Adab. His name also appeared on a textbook of history, but it is now generally believed that he did not contribute to it and withdrew his name after the book received some severe backlash.

In November 1926, Iqbal got elected to the provincial legislative council of Punjab as an independent backed by the Khilafat Conference (his own party, Muslim League, could not participate due to a technical difficulty). He did not seek re-election after completing his tenure of three years but remained an active politician till his death (excepting two years, 1934 and 1935). The famous photograph seen here was taken in Simla (the summer capital, which he visited more frequently after becoming an active politician), most probably by his Sikh friend, Sirdar Umrao Singh Shergill (father of the famous painter Amrita Shergill).

1927-1946: transcendence, and the aftermath

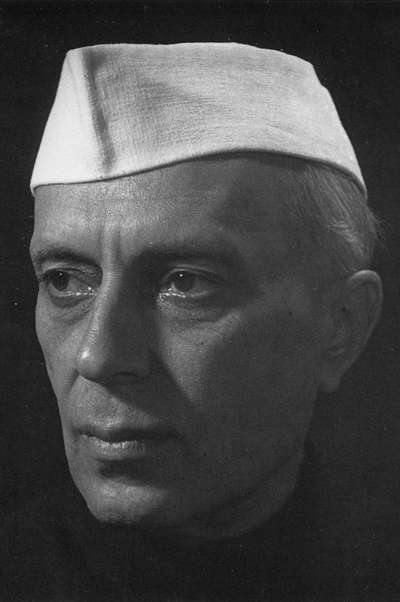

Outside the Muslim electorates, the racial supremacist Hindu Mahasabha (progenitor of the present-day BJP), whose flag is displayed here, secured a landslide victory in the election of 1926 – a few years before its ideological twin, the Nazi Party, came to power in Germany. It did not want the Muslims to choose their own representatives. Therefore, in March 1927, many Muslim leaders jointly proposed that separate electorates could be given up if certain constitutional hindrances, which prevented Muslims from coming to power even in the provinces of their majority, were removed. Most Hindu leaders welcomed the proposals as the true foundation on which an independent India could be conceived, the Indian National Congress adopted them through a landmark “Unity Resolution”, and work commenced on producing a draft constitution on this basis. Surprisingly, the resulting draft, popularly called the Nehru Report, ignored this understanding and seemed heavily influenced by the Mahasabha. It was quickly accepted by almost all other Hindu parties (notable exceptions included the deprived class known as the ‘untouchables’, until they were coerced by Gandhi through a political blackmail in 1933), a situation not very different from Germany, where political groups other than the Nazi Party were either declining or were being absorbed. When the Muslim leaders invoked the earlier understanding, they got snubbed.

From this point onward, the Congress became a mouthpiece of the Mahasabha, although at times doing lip-service to liberal ideas (much in the manner of the Fascists who formed an alliance with the Nazis in Europe a little later). Iqbal would spend the rest of his years fighting this evil in the Indian subcontinent while also trying to liberate the region from foreign domination.

From 1927 to 1933, Iqbal remained at the forefront of politics, often as an office bearer of the All-India Muslim League. He cooperated with the Simon Commission, supported the demands presented by the All-India Muslim Conference (a platform that existed from 1928 till 1934, so that all representatives of Muslim public opinion could take unanimous decisions), and presided over the sessions of Muslim League held at Allahabad in 1930 and of Muslim Conference held in Lahore in 1932. Interpreting the collective will of the Muslims, he foretold the birth of a consolidated Muslim state “at least” in the North-West of India (a prediction that came true with the birth of Pakistan in 1947, and remains true in spite of the exclusion of Bangladesh in 1971). The political ideal he presented to his people was ” live and move and have your being as a single individual.” The only method, according to him, was that ” the Indian Muslims should have only one political organization with provincial and district branches all over the country [and] its constitution must be such as to make it possible for any school of political thought to come into power, and to guide the community according to its own ideas and methods.”

Round table conferences of Indian politicians and British leaders were held in London in 1930, 1931 and 1932. The purpose was to reach some agreement about a new constitution (eventually enforced in 1935). Iqbal participated in the second and the third, and placed much importance on the Minorities’ Pact signed between Muslims and all other minorities of India (except the Sikhs), envisioning equality, and freedom from all discriminations based on caste, race, ethnicity or religion.

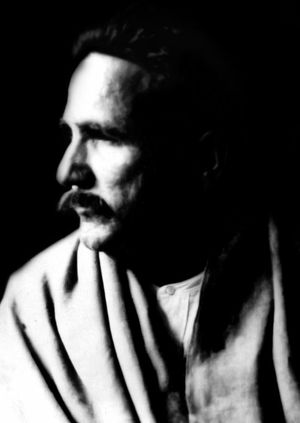

During his last visit to Europe, the iconic photograph seen here was taken by his friend Umrao Singh Shergill in Paris.

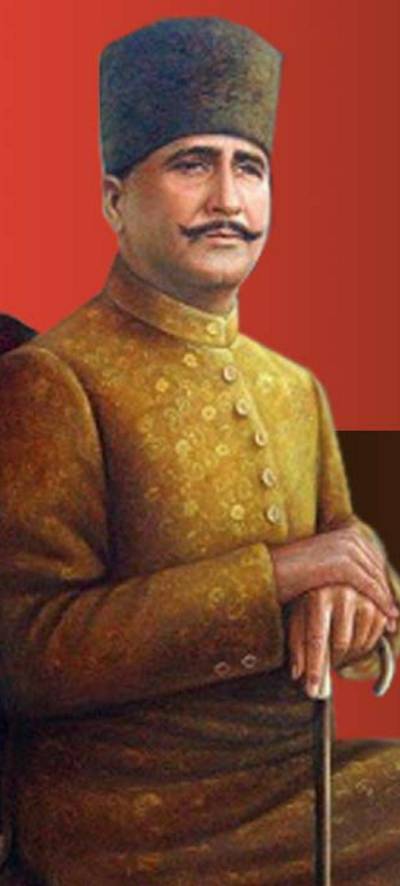

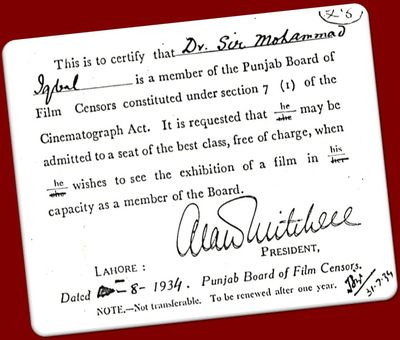

In the 1930s, Iqbal involved himself in an effort to setup a film production company dedicated to healthy entertainment, was a member of the provincial film censor board (his cinema pass can be seen here), and signed contracts with Columbia and His Master’s Voice for gramophone records of his poetry in the voice of commercial artists.

In early 1934, Iqbal developed severe asthma and, sometime later, cataract. He managed to build a house in Lahore in the name of his son Javid, a minor at the time (the house, as seen here, is now Allama Iqbal Museum). Compelled by his illness to give up legal practice, he accepted a generous monthly stipend from his royal friend Sir Hamidullah Khan, the ruler of Bhopal, on the suggestion of Sir Ross Masud, the grandson of Sir Syed. He also visited Bhopal for medical treatment and recuperation, three times in the mid-1930s.

Iqbal had given up politics by the end of 1933, because he believed that his vision could not be implemented unless the entire nation unites under a single political party. Muhammad Ali Jinnah took up this very task in 1934, and on his request, Iqbal returned to politics in 1936 as chairman of the Punjab parliamentary board of the Muslim League and the president of the provincial branch of the party. Reportedly, he also drafted the election manifesto of Muslim League, issued in June 1936 ahead of the election of 1937. He and Jinnah had long been friends, and now they became inseparable in the Muslim imagination.

In the election of 1937, the Congress received considerable support from the Hindu voters, thus capturing several provincial governments, but the Muslims rejected it almost completely (except in NWFP, the present-day KPK province of Pakistan). The Muslim League, although not outstandingly successful, emerged as the largest Muslim party with a countrywide basis. The Congress insisted that only those Muslims would be accepted into provincial cabinets who pledged loyalty to the Congress, even if they had been elected on a Muslim League ticket. Iqbal was quick to point out that constitutional safeguards were not sufficient anymore, and nothing short of a separate state could protect the interests of the Muslims.

By 1937, it had become obvious that those who had come to dominate the Hindu society since 1927 did not want freedom, and wanted to rule over the minorities with the help of British bayonets. Iqbal had said this at least as early as 1930. Seen here in his very last photograph, he now became a symbol of defiance against homebred fascism as well as foreign rule: the call to celebrate an ‘Iqbal Day’ in January 1938 met with unprecedented success throughout British India and in many princely states.

Iqbal passed away in Lahore on 21 April 1938. The funeral procession was attended by scores of thousands from all religions and backgrounds. He was buried outside the royal mosque built by the Mughals, where a tomb was later erected (seen here in the foreground of the mosque). Funeral prayer in absentia was offered at other places. In Calcutta alone, it was attended by over 50,000, and was followed by a condolence meeting where Shaukat Ali said, “Iqbal died with the satisfaction of his heart that he had seen his mission fulfilled.” The meeting was presided over by Jinnah, and an excerpt from his speech is given below.

“Iqbal was undoubtedly one of the greatest poets, philosophers and seers of humanity of all times. He took a prominent part in the politics of the country and in the intellectual and cultural reconstruction of the Islamic world. His contribution to the literature and thought of the world will live for ever.

“To me he was a friend, philosopher and guide and as such the main source of my inspiration and spiritual support. While he was ailing in his bed it was he who, as President of the Punjab Provincial Muslim League, stood single-handed as a rock in the darkest days in the Punjab by the side of the League banner, undaunted by the opposition of the whole world.” (Jinnah, Calcutta, April 21, 1938)

In March 1940, the All-India Muslim League resolved that two federations should be formed in India, instead of one: the Muslim majority areas in the North-West and North-East (approximately the present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, respectively) should form one federation, and the Hindu majority areas another (approximately the present-day India, although the future of the princely states was ambiguous at that time). The details were left to the constituent assemblies of the states after they come into being, but the inviolable principle was that all rights of the minorities in both states should be decided “in consultation with them”. The idea was usually traced back to Iqbal’s Allahabad Address of 1930, but it was also understood that the ultimate source from which he had derived it was the general will of his people (hence, when Jinnah was asked to name the author of Pakistan, he replied, “every Mussulman!”).

The All-India Muslim League contested the election of 1945-1946 on the basis of a single-point agenda, “Pakistan”. It won 100% of the Muslim seats in the central assembly, approximately 90% of the provincial assemblies, and 86.7% of all the votes cast by Muslim voters. Its elected legislators, over 450, met in Delhi on 7, 8 and 9 April 1946, and unanimously passed a resolution reaffirming the demand for Pakistan. A pledge to obey the Muslim League was taken, first by all legislators including Jinnah, and afterwards by the Muslim masses across the country. This convention had originally been suggested by Iqbal a year before his death.

1946-1947: an outcome

In December 1946, a constituent assembly was inaugurated to frame a constitution for a united India, contrary to the Muslim demand. All the Muslim members, except three, belonged to the All-India Muslim League but they refused to join. The deadlock compelled the British government, on 20 February 1947, to agree to the partition and also to announce, for the very first time, a definite date of departure: no later than June 1948. Subsequently, the last viceroy Lord Mountbatten (pictured here with Jinnah and Lady Mountbatten) transferred power to Pakistan on 14 August 1947, and to India on 15 August 1947.

Thus freedom came to India only when the Muslim League, single-handedly and against stiff opposition from its rivals, succeeded in following the steps which C. R. Das had proposed in 1922-1923, being the practical implications of the conceptual framework of Iqbal, who spent the latter part of his life in an effort to make them happen.

In his toast to King George VI (pictured here), Jinnah as Governor-General of the new state said: “This decision of His Majesty’s Government will mark the fulfilment of the great ideal which was set forth by the formation of Commonwealth with the avowed object to make all nations and countries which formed part of the British Empire, self-governing and independent states, free from the domination of any other nation … it falls to the lot of King George the Sixth, the good fortune of fulfilling the promise and the noble mission with which his great-grandmother assumed the reigns of this subcontinent nearly a century ago … There lies in front of us a new chapter and it will be our endeavour to create and maintain goodwill and friendship with Britain and our neighbouring dominion Hindustan along with other sister nations so that we all together may make our greatest contribution for the peace and prosperity of the world.”