Dawn, Tuesday Review, February 27-March 4, 1996

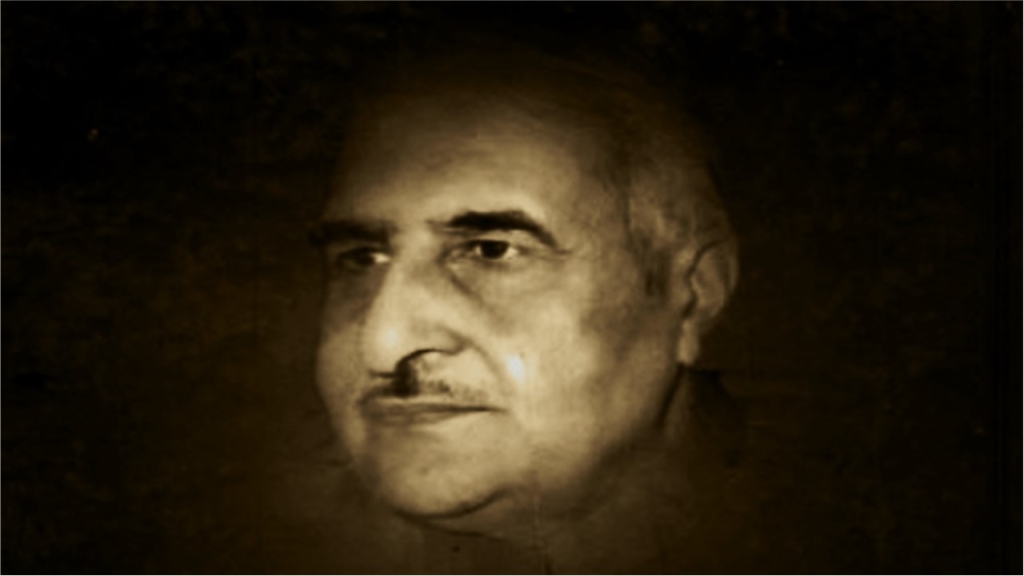

Dr Qureshi evaded my request for his resume in a light vein. “There have been so many interviews about my life. Why not base this one on my thoughts alone?”

Dr Qureshi evaded my request for his resume in a light vein. “There have been so many interviews about my life. Why not base this one on my thoughts alone?”

And which of his works would he consider to be the pinnacle of his thought, the best fruit of his academic pursuits?

“Mein awara kharam aadmi hoon (I am a vagabond). My work is scattered (in all directions?). I began in 1943 with poetry. Two anthologies have been published (Naqd-i-Jaan and Alwah). A third one is on its way. I have been writing in Persian. I taught Punjabi for twelve years and I have written in that language also. Then I worked on Urdu criticism and research – history was my basic subject. I remained a teacher of history for fifteen years. I have worked on the later Mughal period and the history of Punjab. I have a book on the Pakistan Movement: Ideological Foundation of Pakistan. I have been interested in education. Those essays of mine are also being published in a book form now. Iqbaliat [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][Iqbal Studies] was my topic. I remained on the Ghalib Chair in the Punjab University for two years. For another couple of years I occupied Hameed Nizami Chair (I had taught journalism in the Punjab University to its first MA class). Hence I became a scattered person. And the truth is, I do not find strength to work on a new project just now. I am rather trying to put into order what I have already done so far in so many different directions (nothing less than 72 publications!) But to say which one of these is my greatest achievement is difficult. I am not sure if any of these is a great achievement at all. Health and life granted I may be able to do that in future.”

Let me explain here that diversified as his interests may seem, Dr Qureshi’s ideas amount to nothing less than a program for a total reform of our culture. In our 90 minute dialogue he spoke on languages, politics, research and religion. But the thread that ran through all these diversions was the basic idea that there is a need for every Pakistani to know the common heritage and to build her or his career on this particular foundation.

“I believe that the English language, in a way, is our mujrim (the culprit). I have no problem accepting English as a second language but I do not think it has any business becoming a part of our social life, our private correspondence, our wedding invitations, our visiting cards…” He actually refuses to attend a marriage ceremony if the invitation is printed in English. And he always has two sets of visiting cards – one in Urdu for general use, and another one in English to be extended to foreigners only. “In a society where the literacy rate is officially around 23 per cent and in reality only 11 per cent you can hardly justify the use of English on such occasions. We should not stoop to such tricks for asserting ourselves as prestigious and educated.”

This obviously links with education. He is not happy with English being taught from grade 1 in primary schools. “Instead of providing a uniform education to our children we have given them systems which are divided on the basis of language. As a result we have got class alienation. Now the language is no more just a mark of your association with a particular region. It has become an identity of nationalities. And of classes, above all. The child who has been brought up through English medium, lives in one world, and the one brought up through Urdu medium lives in another. To worsen the situation, we have put every student to learn several languages. (English, Urdu, regional language and Arabic). The best part of our intelligence is being spent on learning languages rather than learning the subjects.”

What do you suggest?

“English should be taught as a compulsory second language, perhaps from grade six onwards. The standard of teaching should be improved and more emphasis on functional English rather than literature but we must also remember that English no longer holds monopoly over all scientific information today. Since 1970, and the “blast of knowledge”, only 50 per cent of the modern knowledge is coming through English. The rest is coming through Japanese, Chinese, Russian, French. I consider that a diploma in two or three languages should be a requirement for MSc.

“I do not have any ready formula for reaching a compromise between the regional languages and Urdu, but I feel that the teaching of Urdu should be uniform in all regions, beginning with the conversational and then moving on to information content.”

And in this wonderful worldview does he see any role for Persian, the dead language of our society?

He begins with the frank tag: “Dekhain jee baat yeh hai keh … (and continues in Urdu, like the rest of this interview, which I am translating here) once we had some know-how of Persian, which we used to learn in our schools. The result is that we are able to teach some correct Urdu. When Persian and Arabic were taken out from our curriculum later on, the Urdu teacher became more and more superficial. Just as the teaching of English is not completed until you have studied a little bit of French, Latin and Greek, so the study of Persian and Arabic is important for a profound understanding of Urdu. We should know at least that much of Persian which enables us to understand a stray Persian sentence or verse that may occur in choicest Urdu.

“And then Persian is not just a language to us. It has been a part of our culture. It is important on that account too. We need to know it even in order to understand certain things about our own culture.

“Besides, there is an indirect influence of languages on every person who knows them. For instance, no language tells you to do good deeds, and to do this and that. But while studying it, some change is likely to occur in your character on its own account. This is due to the cultural background of each language. We have forgotten this altogether and bent upon making a scientist of every man. Our country does not have sufficient resources to make so many scientist so we need to make a decision as to just how many of them do we want! Besides, even a scientist ought to be a culturally refined human being. Only then will he be able to develop a link with the national perspective in the true spirit of patriotism. If we do not do this, our younger generation will grow even more secular. Some study of Persian is needed even in order to restore our religious foundations. However, as a teacher I do not favour all languages being taught at the same time. I think they should be introduced with a gap of two or three years in between.”

I do not know whether Dr Qureshi will agree with this or not, but while speaking to him I felt that he is one of the ‘Iqbalians’ – I mean, one of those members of his generation for whom Dr Muhammad Iqbal embodied a cult. “There was a point in my life when I became an atheist. Iqbal’s poetry brought me back to Islam.”

Does Iqbal have anything to offer to others too?

“Iqbal was the Thinker of Pakistan (Mufakkir-e-Pakistan). And whatever he wrote needs to be considered in the context of our present social problems, our political situation, our economic ailments. Iqbal and Quaid-e-Azam have got a lot to offer us to solve these problems of ours. For instance, today we are talking about Islamisation. Iqbal kept on thinking about it from 1930 to 1938, and has a lot to offer on that account too. He said that the mujaddid (the reviver of the faith) of the present age will be the one who re-edits the Muslim law. He thought that the interpretations of Islam carried out in the mediaeval ages were good for those ages. Now we need to reinterpret the Quran.”

The one question that arises in the mind is, once such an interpretation has been carried out, who is to be held responsible for enforcing it in a modern democratic state like Pakistan?

“The thing is that Iqbal did give a lot of time thinking about this issue. In 1930 he said that since Khilafat has been abolished in Turkey now we do not need it. This idea he had taken from Turkey. Later on he became doubtful. Then he said that an Assembly consisting of a majority of people who do not understand Islam, cannot play the right role (in a Muslim majority society). There are such hints in his letters. For example, he says that there should be an institution of ulema (religious scholars) who could be consulted about things presented in the Assembly. Then those ulema should be actively involved in the Assemblies. But there he also points out a possible danger: lest the Islamic state be turned into a theocratic state. Therefore he gives the ulema the right to interpret but wants to hold back from them the right to decide. He is not clear about who should be given this right.

“On yet another level, Iqbal was aware of the need of a dialogue between the graduates of the madressah and the graduates of modern schools. He believed in the integration of these two systems.

“And then there is the issue of democracy. In one of his letters Iqbal says that he accepts it as ‘the lesser evil’.”

I was interested in knowing what kind of projects does he intend to initiate, now that he has been placed at the head of the Iqbal Academy [Iqbal Academy Pakistan].

Some critics, such as Hossein Nasr, maintain that Iqbal was essentially apologetic and that the integration he tried to seek between the atheistic western philosophy and Islamic learning was a complete failure. Dr Qureshi does not agree with them. “Iqbal was a bit apologetic, it is true. And that, because he came just after Sir Syed. That was a period when there was an attitude of intimidation in the face of western knowledge. But as far as this integration, etc. is concerned, it would be wrong not to acknowledge his success. The objection is held out mostly from the followers of Rene Guenon, down to Hasan Askari. They differ with Iqbal in their perspective on Sufism. They do not see what Iqbal has to say but want in him a confirmation of their own views and when that is missing, they are disappointed. This is the other extreme. We don’t consider Iqbal to be the last word in human thought but on the other hand I don’t think it is fair either to hang him there for general scorn and condemnation.”

“I think Iqbal Academy should take on three types of projects. Firstly, there is a need to popularize Iqbal. To get across his message to every one in Pakistan. I brought out a newsprint edition of Kulliyat-e-Iqbal which is priced at Rs 45/- only. Three thousand copies were sold in no time. Now we are going to reprint it on white paper. But there is also a need to bring out Iqbal’s books with parallel meanings of difficult words, so that it may be understood by those who don’t know the language of Iqbal’s poetry.

“Secondly, I think there is need to pay attention to the electronic media. Iqbal Academy prepared audio cassettes containing Iqbal’s poetry in taht-ul-lafz ((before I joined). But there is the need to present it with music. And also to present it on video. Somebody has sent me his video work on Iqbal’s poems. I have placed it in the Academy. The Iranians are also making films on him.”

At this point I interrupted him to ask whether he sees any possibility of a feature film based on Iqbal’s life?

“Yes, there can be a feature film,” he answered. And how will he respond if the film breaks the idol that we have placed on a high pedestal?

“Well, you will have to do something for the projection. You might remember The Message. They did not show the Prophet. Still they made the film. And even now it is interesting. So what is the harm in experimenting?

“And then, of course, we should also cater to the scholars. There should be research on Iqbal. I have already given assignments to some scholars.”

What kind of assignments?

“Iqbal’s link with other philosophers of the east – such as Ibn-e-Arabi. Iqbal and Sufism, to name another project. But above all there is the need for putting together all his prose writings in a grand kulliyat-e-nasr (Complete Prose Works Edition).

“The problem is that we have turned Iqbal into an object of reverence. We have not tried out his ideas. I think he deserves to be given a chance. He might not have seen what is happening before us today but he had anticipated this to an extent. Iqbal is not the final limit of our thoughts simply because there is no limit to the human thought. Bet let us take what he has to offer, and continue from that point.”

Note: Dr. Waheed Qureshi passed away on October 17, 2009

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]