This is a review of the book Bayad-i-Suhbat-i-Nazuk Khayalan, published in Herald, sometime in 1998

The biographical sketches contained in this book are based on the memories of the author, who had long term associations with most of the celebrities described here. Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Dr. Taseer, Majeed Malik, Noon Meem Rashid, Mohammad Hasan Askari and Ghulam Abbas are only a few of those with whom Dr. Aftab Ahmed, a well-known critic, had close friendships. There are others as well with whom Dr Aftab was less intimate but still a good acquaintance: Dr Khalifa Abdul Hakeem, Patras Bokhari, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Khwaja Manzoor Hussain, Sufi Tabassum, Dr Hameed Ahmad Khan, Professor Sirajuddin and Dr Nazeer Ahmed.

The biographical sketches contained in this book are based on the memories of the author, who had long term associations with most of the celebrities described here. Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Dr. Taseer, Majeed Malik, Noon Meem Rashid, Mohammad Hasan Askari and Ghulam Abbas are only a few of those with whom Dr. Aftab Ahmed, a well-known critic, had close friendships. There are others as well with whom Dr Aftab was less intimate but still a good acquaintance: Dr Khalifa Abdul Hakeem, Patras Bokhari, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Khwaja Manzoor Hussain, Sufi Tabassum, Dr Hameed Ahmad Khan, Professor Sirajuddin and Dr Nazeer Ahmed.

The only exceptions in this collection are E. M. Forster, F. R. Leavis and T. S. Sliot, with whom Dr Aftab Ahmed has only single meetings to his credit. Regardless of the terms of his acquaintance, however, all the sketches are alive with emotion and charged with that particular good insight that is the hallmark of high literature.

Without being irreverent, the author has managed to bring out the many facets of each character, some of them not often mentioned by others: the eccentricities of Leavis, the student-like humility of Eliot, the paranoia of Rashid. Through this book, we are also reminded that Patras was less than zealous about literary pursuits, which were never to him a devout passion to be consumed with but only fragrant flower to wear on the collar of his charismatic self. Dr Aftab also points out that Faiz was in many ways a ‘ladies man’ as well as a thorough gentleman. Meeraji is also redeemed, at last, from the psychotic cell where Manto had placed him in the early 1950s – the sketches by Dr Aftab are as lively as Manto’s, only that they are written in a soberer and restrained manner than what Manto would have ever wished or adopted.

The most interesting sketch, however, remains that of the lesser known celebrity, Professor Sirajuddin of Government College Lahore (and also the vice chancellor of Punjab University at one time). Indeed, it is difficult to say why this piece should not be considered a true short story. The character is well established with his anglicized mindset, his cool detached mannerism and his calculated mastery of teaching skills. The development of this singularly gripping character is also well documented through the incidents happening around him as well as through the influence of the people in his life.

Next in richness are the pieces about Ghulam Abbas, N. M. Rashid and Faiz – all of whom were on very intimate terms with the author (even though intimacy is perhaps not the right word to describe anybody’s relations with a mercurial character like Rashid). The secret, as well as known, loves of these writers are described, alas, with the same restraint and decency which is the trademark of Dr Aftab. While most readers will appreciate his decision not to divulge many of Faiz’s secrets, some may also feel disappointed that there is no new light shed on events which might have played a significant role in the life of this genius and actually have been the inspiration for some of the poems many have loved. Geniuses, after all, become public properties.

The overall contribution of this book is in its reconstruction of the literary world of this region from the late 1930s to the mid-1980s. The 15 biographical sketches (describing 18 personae) and the two essays about the literary circles of Niazmandan-e-Lahore and Halqa-e-Arbab-e-Zauq build up a breathtaking collage of life as it was seen and lived by some of the most eminent personalities of our literary and academic scene.

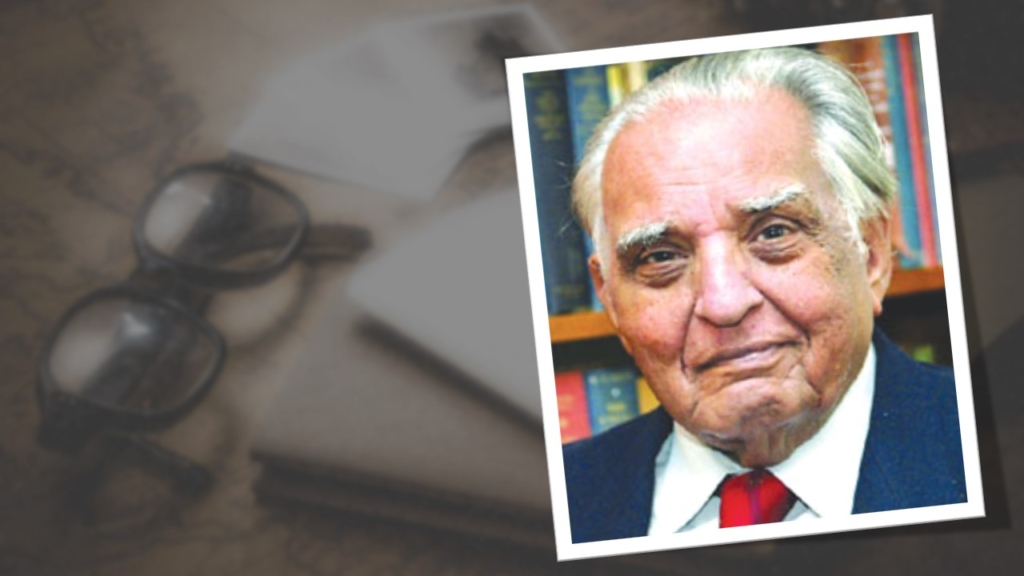

Only a skeleton of the author’s own career can be traced, however, through the essays included in this book: from his birth in a family that was closely related to the famous Zafar Ali Khan, through his student life at Government College Lahore, and his later progress in his bureaucratic career. What does come through is an impression that Dr Aftab was a ringside observer, and sometimes a participant, in most literary happenings of the era. But he has remarkably refrained from any attempt to make himself prominent at the cost of the people he is writing about. That he is himself a reputed critic with a claim to some well-known books on Ghalib, Iqbal and Meer, as well as on contemporaries like Faiz, Rashid and Askari, is a fact that finds mention only on the inside back cover.

The narrator in these essays appears as significantly unassuming – the only reason we cannot compare him with Arthur Conan Doyle’s Dr Watson is that his role in the narrative is far less active. Of course, careful editing could have avoided some repetitions (such as the episode about Dr Aftab’s recruitment to the foreign service, which pops up in almost every alternate essay). Cross-referencing is another device that we miss sometime while reading this book – but not very much, actually, since the other graces of the work go far beyond just saving the show.

The only part which lies pathetically in need of help is the somewhat verbose preface written by Mushtaq Ahmad Yusufi. Good editing could have done wonders for it, especially if it were carried out in the light of the principles of good prose that Mr Yusufi himself establishes in the preface.