Iqbal believed that if Iran were to lose its independence, it would not just be a loss for the Iranians. The impact on the world of Islam would be much more disastrous than the Fall of Baghdad in 1258 (by far the worst tragedy in the history of Islam). I am listing some of the most significant and substantial references to this country, its role in history and its destiny as they appear in the writings of Iqbal.

The mind of Iran

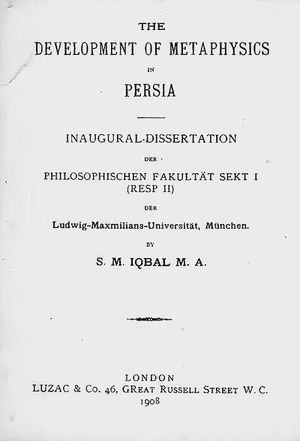

The topic of the PhD thesis of Iqbal was The Development of Metaphysics in Persia. Published from London in 1908, it was the first detailed study of this topic.

Although Iqbal later wrote that this work had become obsolete in most parts, he had nevertheless managed to establish here some of the precepts which would be retained by him even in his later writings. To mention just one of those:

The most remarkable feature of the character of the Persian people is their love of Metaphysical speculation.

Iqbal, “The Development of Metaphysics in Persia” (1908)

Iqbal perceived the Europeans, the Iranians and the Indians as branches of a common Aryan ancestry (and having descended from the Brahmins of Kashmir, he must have counted himself in the same lot too). He believed the two fundamental principles of this common Aryan ancestry to be that (a) there is law in Nature; and that (b) there is conflict in Nature.

The peculiar manner in which the Iranian mind might be different from the two other Aryan cultures in its treatment of this common theme was later discussed by Iqbal in greater detail in “Islam as a Moral and Political Ideal” (1909) with reference to the Zoroastrian worldview; and in certain parts of Javid Nama (1932), especially through representations of Zurvan, Sarosh, Zoroaster and Quratul Ain Tahira.

These details seem to have evolved from a basic observation which Iqbal had already shared in his Development of Metaphysics:

It seems to me that the Persian mind is rather impatient of detail, and consequently destitute of that organizing faculty which gradually works out a system of ideas, by interpreting the fundamental principles with reference to the ordinary facts of observation.

Iqbal, “The Development of Metaphysics in Persia” (1908)

It seems that Iqbal regarded this tendency of the Persian mind to be a balancing factor in the evolution of the Asian culture in general, and the Muslim culture in particular. It offered him a contrast to “the awful sublimity” of the Indian philosophy. In the sphere of Islam, it seemed to have complemented “the thoroughly practical genius of the Arabs” (a point to be explained further under the heading “Contribution to the uniform culture of Islam” in this post).

Some of the readers might be familiar with my argument about an inherent connection between the work of Iqbal and the subsequent uniform culture of Pakistan. To them (only), I would like to mention that the trait of the Persian mind described by Iqbal is also reflected in the Iranian characters presented by Ibne-e-Safi in his novels Khoonraiz Tasaddum and Shahbaz Ka Basayra; and in the songs written by the Pakistani poets Nasir Kasganjavi and Sehba Akhtar for being filmed on Iranian talents, respectively, in the movies Jaan Pehchan (1967) and Operation Karachi (1970).

The separation of the Church and the State

The separation of the Church and the State means that there should be two parallel authorities, respectively representing the affairs of the world and the affairs of the Hereafter. This arrangement is most commonly associated with Christianity, but Iqbal believed that the underlying philosophical idea came from the pre-Islamic Persian thinker Mani (215 AD – 277 AD).

The philosophy of Mani was discussed by Iqbal in detail in The Development of Metaphysics in Persia, while its influence on Christianity was mentioned by him later in the Allahabad Address (1930).

Interestingly, Iqbal also believed that the Shiah doctrine of the absence of Imam was “a clever way of separating the Church and the State”. The doctrine prescribes that the state really belongs to the absent Imam. The worldly rulers are therefore merely the guardians of the country. Their authority is limited by the authority of the Mullahs, who are the representatives of the absent Imam. This means a greater role of the Mullahs in the Shiah society than is common in the Sunni societies (just as the clergy once played an exceptionally significant role in the Christian states, where also the Church had been separated from the State). This observation, offered by Rousseau perhaps for the first time, was shared by Iqbal in his research paper “Political Thought in Islam” (1908).

In a later paper, “Islam and Ahmadism” (1936), Iqbal also explained how the separation of the Church and the State in Iran is different from what is often called “secularism”, i.e. the presumed exclusion of religion from the public sphere.

Without going into further detail here, we may observe that in the case of Iran (and not unlike the medieval Christian societies), the separation has given more power to the religious authorities, rather than less.

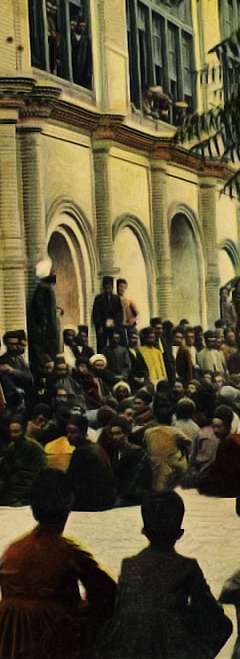

Referring to the Constitutional Revolution of 1906, through which the Shah of Persia had been forced to accept a constitution and to start holding elections, Iqbal could not fail to observe that the Mullahs had taken an active part in that movement. The same can be said about the Iranian Revolution of 1979, through which monarchy was eventually abolished altogether, and Iran became a republic.

The conqueror of its conquerors

It is implied in the statements of Iqbal that the Iranian culture has been the conqueror of its conquerors.

Alexander the Great became thoroughly Persianized as soon as he conquered Iran in the 4th Century BC, and so did many other Greeks afterwards.

The Byzantine emperor Galerius sacked the Sassanian capital in 298 AD. Subsequently, Europe became radically transformed through “the duality of spirit and matter”, an idea originally proposed by the Persian thinker Mani who had passed away some time earlier (the point has already been mentioned above with reference to Iqbal’s Allahabad Address).

Likewise, the conquest of Persia by the Arabs in the 7th Century resulted in a transformation of the Muslim culture (to be discussed as the next point). Something similar happened to the Mongols, soon after they had overrun Iran in the 13th Century: they converted. Writing in 1911, Iqbal insisted that Iran had not lost its peculiar power of transforming those who would come in contact with it: “the people whose contact transformed the Arabs and the Mughals are not intellectually dead.”

Contribution to the uniform culture of Islam

Iqbal has tried to show that the continued existence of the global Muslim community is ensured by three factors. The uniform culture of Islam is one of them. While the source of this culture is the Quran and the impact of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), the most significant role in its making has been played by none other than the Persian mind:

Persia is perhaps the principal factor in the making of this culture. If you ask me what is the most important event in the history of Islam, I shall immediately answer, the conquest of Persia. The battle of Nehwand gave to the Arabs not only a beautiful country, but also an ancient people who could construct a new civilization out of the Semitic and the Aryan material. Our Muslim civilization is a product of the cross‑fertilization of the Semitic and the Aryan ideas. It inherits the softness and refinement of its Aryan mother and the sterling character of its Semitic father. The Conquest of Persia gave to the Musalmans what the Conquest of Greece gave to the Romans: but for Persia our culture would have been absolutely one-sided.

Iqbal, “The Muslim Community – A Sociological Study” (1911)

Due to this reason, Iqbal said that if Iran were to lose its independence, it would not just be a loss for the Iranians. The impact on the world of Islam would be much more disastrous than the Fall of Baghdad in 1258 (by far the worst tragedy in the history of Islam).

In 1911, when Iqbal wrote his paper “The Muslim Community – A Sociological Study” (1911), Iran was being threatened by the Russian aggression just as it is today by a conflict with the United States.

In the following words of Iqbal, if we replace “Russia” with “the United States”, and “the Royal family of the Persia” with “the people of Iran”, the words become as relevant today as they were 109 years ago:

Persia, whose existence as an independent Political unit is threatened by the aggressive ambition of Russia, is still a real centre of Muslim culture, and I can only hope that she still continues to occupy the position that she has always occupied in the Muslim world. To the Royal family of the Persia the loss of the Persia’s political independence would mean only a territorial loss, to the Muslim culture such an event would be a blow much more serious than the Tartar invasion of the 13th century.

Iqbal, “The Muslim Community – A Sociological Study” (1911)

“Magianism”

In the works of Iqbal, Iran appears also somewhat like an epic hero struggling to overcome a big challenge from within. This challenge seems to be related to the same subjective approach that has turned out to be its great strength at times, as already mentioned above. In the periods of decadence and political weakness, it can become a tragic flaw. One of the terms used for this issue in the days of Iqbal was Magianism (different from its current usage as a study of the teachings of the priests of the ancient Iran).

Iqbal has discussed various aspects of this problem in several of his writings but the most sustained discussions can be found in his long Persian poem Secrets and Mysteries (1915-1918) and his lecture “The Spirit of the Muslim Culture” in The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam (1930-1934).

My own researches, proceeding on the foundations laid down by Iqbal, have led me to think that this dreamy-eyed escapism, often associated not only with Iran but generally with the East, might have to do with the fact that one of the most important chapters in the history of Iran was practically erased from the memory of the East sometime at the beginning of the first millennium after Christ. This is a topic which I hope to cover in a future book, Cyrus the Great: His Life and Our Times.

However, the most important thing to remember is that the living source of this “slow-pulsed Magianism” in our times is not located in the East anymore. Since the end of the First World War a little more than a hundred years ago, this enervating mode of thought is being perpetuated – actively, aggressively and abusively – by the intelligentsia of the West and their universities (as also observed by the British historian A. J. P. Taylor). This is a serious danger against which Iqbal warned his people in 1923, in an anthology of his Persian poems, The Message of the East.

The Shiah-Sunni unity

The long-standing historical differences between the Shiahs and the Sunnis often moderate the relationship between Iran and some other Muslim countries. The works of Iqbal can help us find a way out of this dilemma too.

Iqbal divides the evolution of the political thought in Islam into three phases. In the first phase, comprising mainly of the period of the first two caliphs, there were no political parties. This is the ideal situation, since “the idea of universal agreement is in fact the fundamental principle of Muslim constitutional theory.” The ideal system for Muslim politics is therefore a “national organization” (not to be confused with one-party system, as I have explained elsewhere).

The rule of the third caliph in the second half of the 7th Century was considered by Iqbal to be “really the source of the three great religio-political parties with their respective political theories.” These parties consequently became known as the Sunni, the Shiah and the Khwarij. They have often been treated as religious sects but many scholars have seen the origins of this division in political differences rather than religious. So did Iqbal, to whom the mere existence of religious sects was not a serious threat to the solidarity of Islam, but the existence of political parties was.

The emergence of these parties marked the beginning of a second period in the political history of Islam. During this period, each party attempted to realize its political theory by coming in power in one or the other part of the Muslim world. The struggle lasted for centuries.

An earnest attempt for reducing conflict between the Shiahs and the Sunnis was made by Emperor Nader Shah Durrani, who ruled over Iran from 1736 to 1747. Due to this service to the solidarity of Islam, he is depicted as residing in Paradise in Iqbal’s Persian masterpiece Javid Nama (and quite obviously, Iqbal had to rise above any biases he might have had as an Indian, because the Indians remember Nader mainly as the invader who carried out a horrible massacre in Delhi).

The second phase in the political history of Islam practically came to an end in 1906. This was the year when the political boundaries between the major parties (Sunni, Shiah and Khwarij) either vanished or began to grow thinner. The Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, including the largest congregation of Sunni population, formed their first political organization on a completely non-sectarian basis and chose the Imam of the Ismaili Shiahs to represent them in the process. The same year, Iran adopted the principle of election, which had been the defining characteristic of the Sunni political theory.

The year 1907 was, therefore, the beginning of a new phase in the political history of Islam according to Iqbal. And we can say that we are still in the initial parts of this new phase. This phase is marked by a gradual movement towards the original solidarity of Islam, as observed by Iqbal most famously in his short Urdu poem “March 1907”. In prose, he wrote:

In modern times—thanks to the influence of Western political ideas—Muslim countries have exhibited signs of political life. England has vitalized Egypt; Persia has received a constitution from the Shah, and the Young Turkish Party too have been struggling, scheming, and plotting to achieve their object. But it is absolutely necessary for these political reformers to make a thorough study of Islamic constitutional principles, and not to shock the naturally suspicious conservatism of their people by appearing as prophets of a new culture. They would certainly impress them more if they could show that their seemingly borrowed ideal of political freedom is really the ideal of Islam, and is, as such, the rightful demand of free Muslim conscience.

Iqbal, “Political Thought in Islam” (1908)

The evolution of democracy

Iqbal believed that democracy was the most important aspect of Islam regarded as a political ideal, and the fundamental principle laid down in the Quran is the principle of election. Yet, the republic of the early Islam did not last long and the Muslim countries remained under monarchies for a very long time. One of the two reasons, according to Iqbal, was that “the idea of election was not at all suited to the genius of the Persians and the Mongols—the two principal races which accepted Islam as their religion.”

The awakening in the world of Islam, according to Iqbal, started in the 18th Century – around the same time as the Enlightenment in Europe although progressing at a much slower pace here. Determined “almost wholly” by the inner vitality of Islam, it was nevertheless accelerated by the pressure of modern ideas from Europe in the 19th Century and produced such reformers as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan of India, Mufti Alam Jan of Russia and Syed Jamaluddin Afghani (also called Asadabadi). These reformers revolted against the rigidity of the ulema, the spiritual tyranny of the decadent Sufis and the dynastic rule of the Muslim kings.

After them came the leaders who took practical steps for the political transformation of the Muslim countries. Iqbal makes a special mention of Zaghlul Pasha of Egypt, Mustafa Kamal Ataturk of Turkey and Reza Shah of Iran (not to be confused with his son who was deposed in 1979).

The legacy of Reza Shah is extremely controversial today, and Iqbal could foresee this. In his Urdu verses, he admitted that neither Ataturk nor Reza Shah represented “the soul of the East”.

Yet, he believed that any mistakes committed by these leaders should not become a reason for us to adopt a pessimistic approach about the future of their respective nations:

Such men are liable to make mistakes; but the history of nations shows that even their mistakes have sometimes borne good fruit. In them it is not logic but life that struggles restless to solve its own problems.

Iqbal, “Islam and Ahmadism” (1936)

The subsequent history of Iran, just like the modern histories of most other Muslim countries, is often seen as a series of accidents without any semblance of continuity. In the light of Iqbal’s writings, this approach seems to be unjustified because, as Goethe also wrote in his West–östlicher Divan (a homage to the literature of Iran), “He who does not know how to give himself an account of three thousand years may remain in the dark, inexperienced, and live from day to day.”

The diplomatic centre of the East

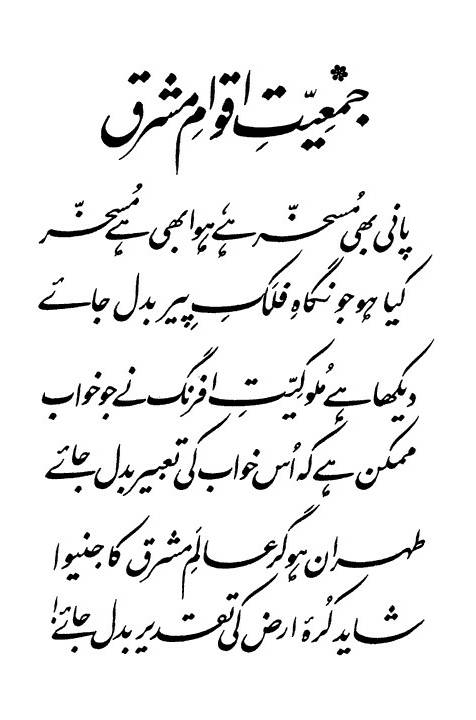

Iqbal believed that a living nation has a fixed destiny, and the events in its life are determined more by this destiny rather than any apparent causes. The destiny of Iran, as he understood it, was described by him in a few Urdu verses in his anthology The Rod of Moses (1936):

The waters and the air have been mastered,

If only Fate could also become favourable now!

The dream that has been dreamed by the Imperialism of the West,

It is possible that the interpretation of that dream might change.

If only Tehran were to become the Geneva of the East,

Perhaps the destiny of the entire planet will change!

The poem is titled “The League of the Nations of the East”. As we know, the League of Nations was the predecessor of the United Nations, and had its headquarters in Geneva. Iqbal seems to be suggesting that if Tehran could become the diplomatic centre of the East, this could lead to perpetual peace in the world.

In view of everything else which Iqbal has said about Iran, and some of which has been shared above, this does not seem to be just a poetic metaphor. It is rather an idea that fits perfectly well with Iqbal’s understanding of the Persian mind, its contribution to the culture of Islam as well as its place in the history of human civilization.

Also, it is an idea that seems to be achievable. The crisis that has been lingering on in parts of Asia for almost a decade and has recently escalated into a show of open hostility between Iran and the US might eventually pressure the nations of the East into realizing this dream of Iqbal just as the First World War pressured the nations of Europe to form the League of the Nations, and the Second World War resulted in the birth of the United Nations.

Let’s hope that we are not witnessing the beginning of the Third World War. But another world war or not, a sustainable unity of Asia with Tehran as its diplomatic centre appears to be rather predestined in the light of the observations which Iqbal has shared through his writings.

Interesting facts about a nation. More astonishing factor is that it has been able to retain the magic even after much turmoil. I found the passage “Conqueror of the conquerors” most fascinating. I hope we pay heed to the ideological father of the nation.

Thank you for the enlightening article.

Very timely a thought provoking effort.