Dawn, Tuesday Review, March 5-11, 1996

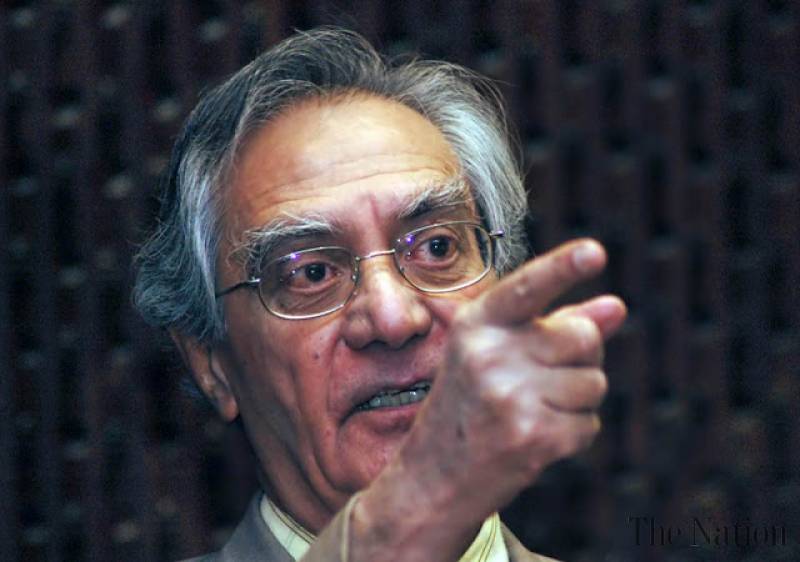

If you ask me to describe Aslam Azhar in a single word, I would describe him as a ‘reader’. Not only because he is a reader of books but also because he is a reader of the signs of time. He has tried not only to read into the meaning of whatever is around him, but also to read his own soul.

If you ask me to describe Aslam Azhar in a single word, I would describe him as a ‘reader’. Not only because he is a reader of books but also because he is a reader of the signs of time. He has tried not only to read into the meaning of whatever is around him, but also to read his own soul.

“I somehow learnt very early, I suppose through accident, to, as far as possible, think, feel and live a little bit unconventionally. This has helped me to clear my ideas a lot. I don’t claim that they are right ideas but at least they are new avenues of approach. Now it is upto the others (to decide) whether what I am saying is rubbish or whether it makes any sense. And then, our truths are only truths of the times, they cannot be truths of all times. Pohnchay huvay loge to hain nahin.”

Pohnchay huvay loge means ‘the chosen ones’. In the spiritual sense, of course. Indeed, anyone who speaks to Mr Azhar these days can be sure to find a lot of allusion to the sufi terminology. This is partially due to the sufi texts that have comprised almost his sole reading for a long time now and partially due to the changes these texts have brought in his outlook of the world. There have been radical changes, his friends will tell you. For instance, he has come to believe that the electronic media is a sign of deviance and little good can come out of television or film no matter how you use them. This from the mouth of someone who has made a niche in our cultural history as one of the godfathers of television! Ask him to justify this change and he will say, “Do I have to justify? It would have been a disaster for me had I not changed over all these years. Whether I have changed for the better or for the worse would be a subjective value judgment. But in my own opinion I have increased.”

But what is his case against the electronic media?

“My case against them is that they present everything in a predigested form. I will explain what I mean by ‘predigested’. When I write a story in print and you read it, there is much that I can only suggest to your mind. I can describe a situation with which you may be unfamiliar. But I cannot bring to you the colours of that situation, the smells of that situation, the feeling and mood of that situation. That comes from your imagination — from the reader’s imagination. So in reading or in listening to a story, the reader or the listener is constantly exercising his own intellectual powers. His powers of imagination, reasoning and understanding. When I tell the same story on television (or film) I paint the most vivid pictures. I show you the close ups of a woman in pain who has been raped. I show you the agony on her face in big close ups. I predigest the entire situation for you. And what is left for you to do? Nothing. Except take it in, in a state of sleep. I wrote a long essay on this, some forty or fifty pages, in which I argued that the viewers of television and commercial cinema are viewers who sit in front of the screen in a state of sleep. Which is the way we go through life, actually, and the impressions that we receive are taken in by us. We are not actively involved.”

And this state of sleep? Does he connect it with the sufistic paradigm of the levels of consciousness?

“Well, that’s at a much higher level but even at an everyday level, even normal human beings (who are far from being illumined in the spiritual sense) need to be sometimes woken up. But I maintain that coming out of this consumer industrial society, the medium of television is designed to keep people asleep – not consciously, but this is the effect in the end. And this is one of the reasons I say that the audiovisual media will never actually succeed in replacing the print and the spoken word. Because inside each human being there is some kind of a little stirring — though it may be subdued — to be woken up. Just as a human being wants to use his muscles; he wants to walk; he wants to be active; in the same way every human being understands that now and again he must exercise his mind and heart. Therefore print, books and the spoken word will never be eliminated.”

Pronouncing the verdict of damnation against television and commercial cinema, he unfurls a protective umbrella to cover theatre, documentary and art cinema with his blessings.

“In theatre also your powers of imagination are constantly exercised because (in front of you) is just a stage, just a set, and there are those characters. Everything else you have to imagine. Read the prologue to Shakespeare’s play Henry V. There he says. ‘Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts. Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them / printing their proud hoofs, carry them here and there…’ etc. In other words, Shakespeare was very conscious that the theatre audience is not to be a passive audience — that is why theatre never disappeared.”

And what about the documentary and the art cinema?

“Documentary does not make any claims as a form. Documentary, as a form, only conveys information, and leaves the rest to you to use the information or discard it. Hence it does not ‘put you to sleep’ in the same sense that all these other products of the so-called imagination do.

“Now we come to the art cinema. The good exponents of art cinema try to wake you up, which makes it an entirely different genre, so you will observe that these art movie-makers are very unconventional in treatment, dialogue, visuals, editing — sometimes they deliberately choose black and white so as to give your powers of imagination a chance to be exercised. Now the questions is, does (the art movie-maker) wake you up in a way that illumines you or does he wake you up in a way that disorientates you. There are many an artiste who make you up, but in doing so they give you such a shock that you are disorientated. For instance, these surrealistic paintings of Salvador — or to say what Ingmar Bergman is doing to us, what Kurusava is doing to us, will be a subjective judgment from me. For, to tell you the truth. I am no expert on them. I have watched their movies but not in a very critical way.”

Although he holds back his judgment on these directors, I get a feeling that the very fact that he mentions them and admits having seen several of their movies means that he does not find them disorientating altogether. For he avoids undertaking experiences that could put him at a risk of ‘disorientation’.

“I do not listen to classical music, eastern or western,” he says, “because I do not know what it will do to me.” One exception is Samuel Bach, whoe Art of Fuge he would recommend to any beginner. But why Bach? “I think that he lived in an age when the human being had just started to go astray, I would say. So, there is purity in Bach’s music. And his use of point/counterpoint is, I would say (spiritually) exalted. I feel as if I am listening to Pathaney Khan.”

If you ask him to explain the difference between illumination and disorientation he would refuse with a note of humility. “This is too big a question for me. I can only see its impact on myself. But I cannot translate it for someone else.” Almost in the manner of a sufi novice, he referred me to another friend of his, saying, “he might tell you. He has read more than me, and he sits in the company of that sufi master…”

While Mr Azhar stops to refill his tobacco pipe, I have a chance to register the titles of the books that are lying at his arm’s stretch. Ibne Arabi’s Bezzels of Wisdom (Suhail Academy edition) and An Introduction to Sufism by Titus Burckhardt.

“I regret my ignorance of Persian and Arabic, as it stops me from approaching the texts of the masters in original and I have to rely on the translators. If the translator has failed to grasp a point, I will never come to know that the master had actually said that at all… That’s the problem with translations.”

What about Iqbal? Does he enjoy reading the Poet?

“No doubt, and he inspires too. But he is ultimately a social poet. He does not take us to the venues I would like to visit. Although he has written poems like Rumooze Bekhundi, but he merely points at (the spiritual dimensions) and passes on to tackle the more social issues. Then, of course, the other thing is that he places the human being at a higher altar. Now, the human being is ashraful makhluqat, (a higher being) we agree. But there are other aspects too. For instance, when Ibne Arabi says that in the cosmos the highest status is that of man, and then there are the animals, and then the vegetables, and then the minerals. And without any doubt, in terms of his possibilities, man is the greatest and he alone has been created in the image of God. But at another level, the further down we go in this hierarchy, from man to animal to vegetable, the more you find that between the manifestation of the species and the manifestation of an individual within that species there is less and less of a distance or gap. Animals participate in the macrocosm more perfectly than man does, because one cow is like all cows and contains within itself the characteristics of a cow. One tree retains the characteristics of all trees.

“But one human being — because the individual has been given autonomy by God — uses that autonomy for both good and evil. When he uses it for evil he distances himself from Him as a specie, and when he does that he is not able to participate in the macrocosmic universe, because he has adulterated himself. Iqbal does not speak of this. He places man on the throne (and says) you’ll achieve this, and you’ll achieve that. But man does not, because he is steadily increasing his distance from his source. I sometimes think that this is why each prophet who came after, brought an even more urgent message than his predecessor. The message of Muhammad (PBUH) is more urgent than the message of Moses and Abrahan.”

To borrow a phrase from Lord Northbourn, Mr Azhar is now ‘looking back on progress’. He remembers with admiration their household servant from his boyhood days, who would sit by the radio and listen to pure classical Indian ragas. It is a sign of decadence, that the common people today are no longer able to take pleasure in such activities and instead stoop down to listening to cheaper stuff – ‘Super jhankar?’ I felt like commenting.

Then there was his maternal grand-father. He was an expert in the traditional eastern medicine as well as in the western allopathic, for which he had even acquired an MBBS. And people would still insist that he give them the eastern medicine. Not today. The attitudes have changed. We have moved further from our origins. And the west has to take some of the blame. Through colonization they have introduced the same “divorce of intellect and heart” which they had developed as a result of the renaissance. And what have we got instead? Progress? Literacy? Education? Aslam Azhar doubts that. “There has been research to show that the literacy rate in Punjab was around 85 per cent in the mid-nineteenth century. And then in British came. And they tried to ‘educate’ us. When we finally got rid of them in 1947, the literacy rate had dropped to 13 per cent! Now, how can one believe in progress? And if Europe has ‘progressed’ over these four hundred to five hundred years, has it increased the understanding or put it at an abeyance? There was always a curtain, I believe, between the human being and the truth. But I think that this curtain has become all the more thicker and darker for them through their ‘progress’. But not so for my villager. Whether he is a Pakhtoon or a Punjabi or a Sindhi or Madrassi… the curtain between the villager and the truth is not all that dark.

“But NGOs are working on it,” his last sentence is punctuated with his typical disarming laughter, and I know that this was a joke.

Are you suggesting an alternate programme of literacy?

“Well, first of all I insist that the child must be make literate in his mother tongue, be it Pushto or Balochi or Urud or whatever. It is almost a metaphysical power to explore the world. And this power can only come from my mother tongue. And only then will I remain close to my mother culture. And then, as I understand the world, I grow and I will grow without my roots being cut… my nourishment will continue to come to me from the roots. And then naturally as my tree grows and spreads its branches, some branches die. They have to be chopped off — other branches remain healthy. Not everything in my heritage is living. Some of it has died — murjha gaya hai kutchh — if something of my heritage has become irrelevant I will thrash it our. But it ( has to be ) in my mother tongue (so) that I will not be left an orphan.

“Some people say, without English we can’t learn the modern subjects. I am amazed, because when I go to Iran I see people there doing their Ph Ds in Persian. When I go to Korea, they are doing it in Korean. In Nigerian, when I go to Nigeria… it is only our slave mentality which makes us offer this type of argument. If you are really worried about getting your students to do their Ph Ds in Nuclear Physics, then consider this: a child who comes from the village at age ten or so won’t be able to do it at all because you have so confused him with languages. The British have left the peoples of India and Pakistan as orphans — we are neither fish nor fowls.”

I had the pleasure of meeting Aslam Azhar many times during my visits to Islamabad in the 1990s, and this interview was conducted on one of those occasions. He passed away at the age of 83 in Islamabad on 29 December 2015.